Don’t just sit down to write any old thing at any old time. Pick a particular moment to do a specific thing. This will not only help you to do it well; it will make you better at it as you do it.

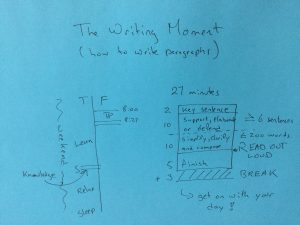

Writing Process Reengineering therefore organizes your writing process into discrete “writing moments”. They normally last twenty-seven minutes and are followed by a three-minute break. Each writing moment produces a single prose paragraph of at least 6 sentences and at most 200 words. A formal writing moment is always planned the day before, specifying when, where and what will be written. Once planned, it should be respected as one would respect a planned meeting or class.

The task can be specified quite precisely. The key sentence tells you what you want to say and I recommend you choose something you knew already last week, not something you just learned today. Pick something you know comfortably. You can then decide what difficulty it poses for your reader, i.e., whether you need to support, elaborate or defend it. You should be clear about what part of the paper you are writing on: whether you are writing background, theory, method, analysis or discussion, or whether you are working on the introduction or the conclusion. You might decide, for example, to elaborate on “Sensemaking is generally taken to be a retrospective process” in your theory, or “The internet has changed how businesses communicate with their customers” in your background section. You might commit yourself to writing in a single paragraph from from 7:00 to 7:27 before you head to campus or from 8:00 to 8:27 in your office when you get there.

Make this decision at the end of the day, when you’re not going learn anything new, not going to get any smarter. Then put it out of your mind. Have a relaxing evening and get a good night’s sleep. Write the paragraph at the appointed time, as the first intellectually challenging thing you do.

“Suffering is one very long moment,” said Oscar Wilde. But your writing moment doesn’t have to be that way. Let the first two minutes be about your key sentence, think about whether it’s the simplest, sharpest way to say it, and notice that (or whether) it gives you some structure for the paragraph. (Does it identify a number of factors? Does it suggest a narrative arc? Does it propose a causal relationship? Does it characterize a population?) Then spend about ten minutes just writing sentences; then another ten minutes making them clearer. Now read you paragraph out loud and fix whatever you can in the time that remains. Or structure the moment differently if that’s what works for you. There are many things you can do and you want to become better and better at doing them.

This gives writing a “here” and a “now” in which to happen. It should be experienced as a kind of freedom (an opportunity to write) not a constraint (a compulsion to write). You know what you are trying to do now, and you’ve given yourself conditions under which you can do it. Now just do it as best you can.

See also: “Composing the Moment, part 1” and “…part 2”, “Seven Little Disciplines”, “How to Make up Your Mind”, “Deciding What You Want to Say”, “Deciding How to Say It”, and “How to Write a Paragraph”.