…a pattern of loss and of finding that so compels us that we are entirely engrosst in working it out, this picture that must be put together takes over mere seeing.

Robert Duncan

For the past few weeks I have found myself in a bit of a slump. I was stuck intellectually without really knowing what was wrong. It was like there was something just beyond the reach of my understanding that I wasn’t able to grasp, and it seemed somehow very important that I grasp it. Then, suddenly, the fog lifted and I could see clearly what I had been struggling with.

I can identify almost the exact moment that things fell into place. “Did something happen to the connection between language and experience?” I had tweeted. I meant this in the same way that we sometimes ask a family member or colleague, “Did something happen to the internet connection?” I was trying to be funny, to be sure, but I also wanted to engage in a little cultural criticism. I can’t be the only one who senses that something is amiss, and what’s Twitter for if not to share our exasperation with the world? Anyway, it was already late, and I was soon in bed and sleeping. But by the end of the next day I had my epiphany. “Now I can go on,” as Wittgenstein used to say. Let me try to explain what happened.

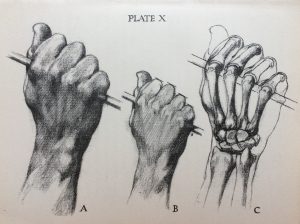

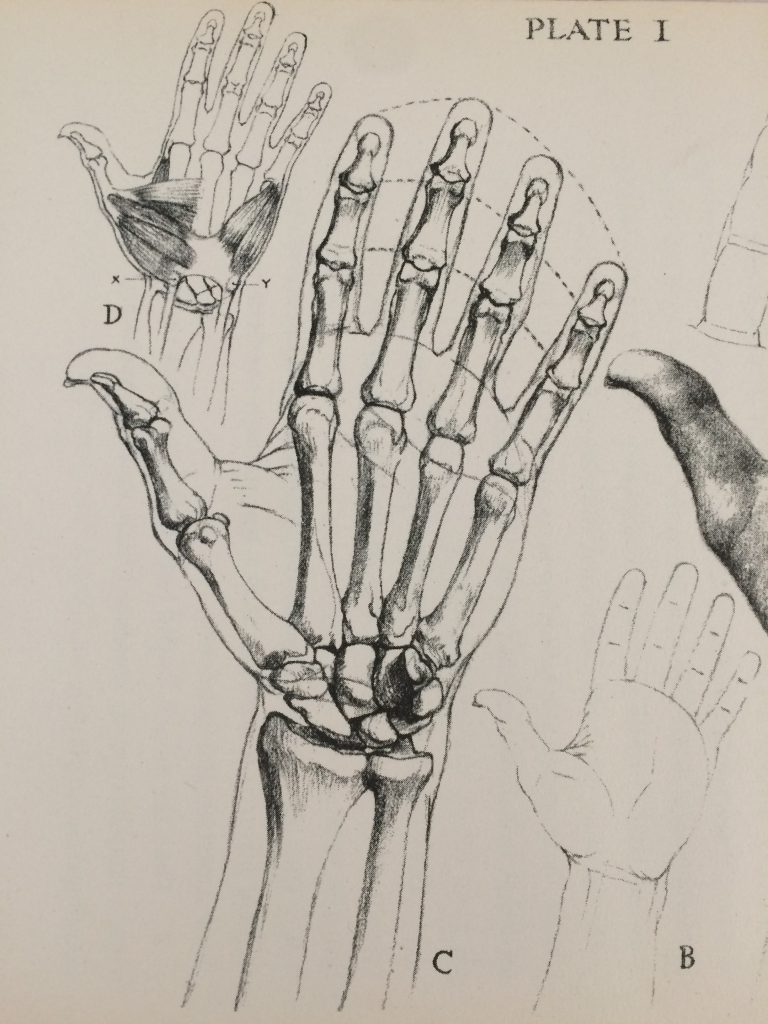

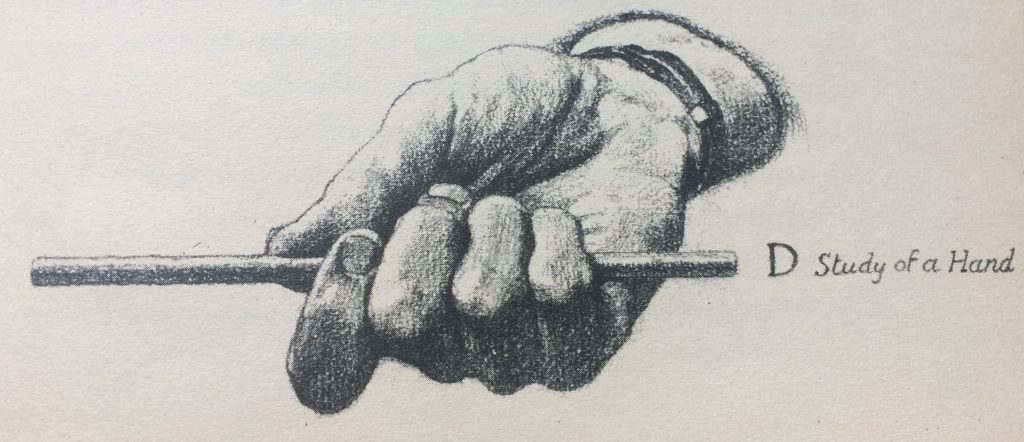

Along with Oliver Senior’s hands, Hemingway’s iceberg is probably the metaphor that dominates my thinking about writing most aggressively. I have used it to organize my teaching of academic writing at all levels, and across a variety of disciplines, and I think writers generally find the image useful. “The dignity of movement of an iceberg,” said Hemingway, “is due to only one-eighth of it being above water.” Most of the knowledge that we base our writing on is not visible to the reader on the surface of our text. But, “if a writer of prose knows enough about what he is writing about,” Hemingway pointed out, “he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them.” It is that knowledge that gives our writing its dignity.

The ideal Hemingway story is a “sequence of motion and fact”. It consists of descriptions of what is happening and what is the case, what the characters do and see, as the action unfolds. These descriptions are what T. S. Eliot called the “objective correlatives” of the emotions that a story is trying to convey. The modernists were sometimes outright purists about such matters and insisted that only these descriptions were legitimate in art; there was no room for explanations, as Wittgenstein also suggested. “Show, don’t tell,” as the saying goes. Don’t tell us the hero was angry, or happy, or sad; show us “the sequence of motion and fact which made the emotion.” Make us feel it too. That was Hemingway’s goal and he knew it would not be easy.

“A writer’s problem does not change,” he said. “He himself changes, but his problem remains the same. It is always how to write truly and, having found what is true, to project it in such a way that it becomes a part of the experience of the person who reads it.” I like this way of putting it, and when I present Hemingway’s iceberg I normally do so in terms of experience rather than knowledge. After all, Hemingway wrote stories, not research papers, and I want to make clear that academic writing is not literary writing but stands in a special relation to this thing we call “knowledge”.

So I sometimes get writers to first imagine telling a story from their own ordinary lives. “What gives such a story its dignity?” I ask them. The obvious answer is: the experience that that the story is based on. If we depart too far from what we actually saw and did (if we start to embellish the story, as we are wont to do) our story may become more exciting, but we are risking its dignity. Someone who has done and seen similar things may find our story implausible.

Then I ask them to think about what makes research papers (and dissertations) different. What plays the role of experience? That answer, of course, is “knowledge,” and this then lets me open a rather big can of worms: What is knowledge? I try to keep things practical and manageable, but what follows is about forty-five minutes of working through the philosophical, rhetorical, and literary dimensions of academic knowledge. Alternatively, I work through the different kinds of knowledge (or the various sources of knowledge) that the individual sections of their papers are based on. I coordinate what is above the surface with what is below.

The epiphany I had this week, however, offers me a more natural transition from Hemingway’s iceberg to mine. It has to do with something I had begun to say already last year, namely, that the methods section is the part of a research paper that is most directly based on your experience; in fact, it’s the section that is most analogous to a short story. Your methods consist of what you did to collect your data. In fact, it’s the story of how you converted what William James called (and Thomas Kuhn recalled) the “blooming buzzing confusion” of experience into data points for analysis. It’s the sequence of fact and motion, if you will, that “makes” your concepts, your measuring instruments, your categories of observation.

Instead of just watching people work, you observed them and recorded these observations carefully in your field notes; instead of just listening to them talk, you conducted semi-structured interviews, recorded them and transcribed them, making them amenable to coding. The data that results has a certain order and formality, which makes it easier to work with in your analysis, than, say, your memory of what happened and what was said, but the experience of collecting the data is just as ordinary and “lived” as any other thing you do during the course of the day.

This is where I now intend to begin my writing instruction. And that’s also the answer to my vaguely rhetorical question on Twitter. Did something happen to the connection between language and experience? Yes. Method happened. The twentieth century has seen the rise of methodologies that increasingly get between our language and the experiences we use it to talk about. This is essentially the same thing as the rise of the social sciences and, by their means, the displacement of literature (poetry, novels, short stories) as means to understand the “human condition”. The imperative of method has made us unsure whether we can just talk about what we saw and what we did, what happened to us, what we think. Perhaps this was a necessary imposition of rigor on our otherwise hopelessly anecdotal lives. But could it be that it has gone a little too far?

I’m going to devote a few posts to this question, which, as we will discover, is the question beneath all the questions that has occupied me for well over a decade. I’m looking forward to seeing where this leads.