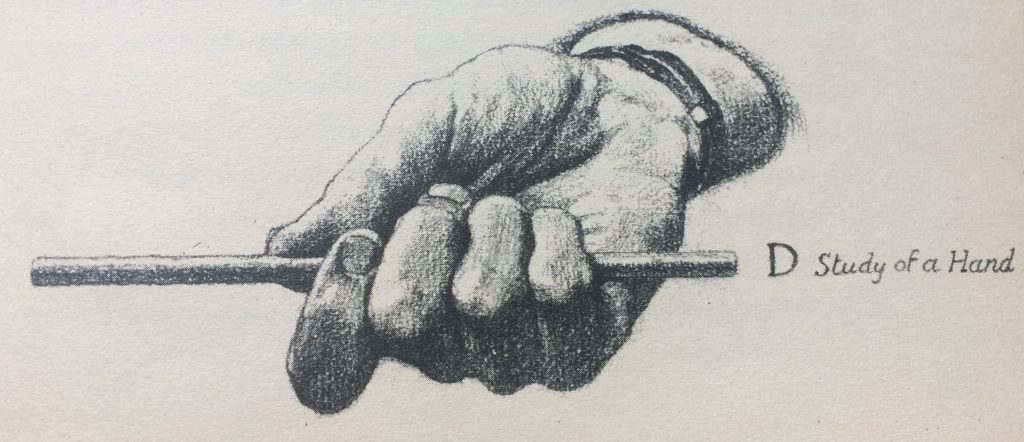

[Note: this post is part of a series on the “substance of the craft” of scholarly writing. Inspired by by Wayne Booth (co-author of The Craft of Research) and Oliver Senior (author of How to Draw Hands), I argue that composition is the coordination of words and ideas, paragraphs and propositions, sentences and the state of things.]

Writing trains you to see ideas just as drawing trains you to see things. “Look at your hand,” I often tell my students, “and imagine drawing it. Now, have an idea, and imagine writing it down.” I then go on (sometimes for hours) to talk about the second half of that last instruction, the problem of writing our ideas down, but I’ve noticed that I leave the first part, “have an idea,” almost entirely out of the discussion, as if it’s as obvious as looking at your hand. Rereading Oliver Senior’s How to Draw to Hands the other day, I realized that I’m actually not following his model as closely as I like to think. He does tell you to look at your hand. But he also tells you what to look for, what to notice in preparation for drawing it.

Hold up your spare hand, then, with the open front or inner surface facing you, fingers and thumb extended but held easily without strain, and look at its odd shape and remarkable system of upholstery as though you had never seen such an object before and did not want miss noting even the most obvious facts about it. (Pp. 10-1)

Senior has the distinct advantage over me that he has a pretty good idea what you’d be looking at if you followed his instructions, even though he’s never met you and never seen your hands. When I ask you to “call an idea to mind,” I have no idea what you’re going to be thinking of, nor how oddly it may be shaped or how remarkably upholstered. You might be thinking of a pricing model or an organizational culture or an aircraft manufacturer. Or you might be thinking of a historical event, a legal framework, or a comic-book villain. Or you might be thinking of an old friend, a dear colleague, or a feared enemy. Or you might… Well, you get the point, having an idea is much more general than holding up a hand, and I think that gets me some way towards recognizing my first mistake.

A while back I did actually have a better idea: think of an interesting place you know well. While I’d still be in the dark about exactly what place you now have in mind, the fact that it is a place would let me give you some meaningful instructions by which, as Senior puts it, your “vision may be directed, extended, and refreshed.” Notice, for example, how big the place is and where its boundaries are. Are those boundaries sharp, distinguishing the place clearly from its surroundings, or does it vaguely “shade off” into its environment? (Is it a room in a house or a clearing in a forest? Is it a section in a cafeteria or a building on a campus?) Is it a place in nature or is it furnished with artifacts? What sort of business is transacted there? How accessible is it? By land or sea? By plane, train, or automobile? Or can you, perhaps, only get there on foot? Is it wheelchair accessible? Do you need a key? Are there particular customs that apply there and are you expected to wear an official costume? How do you know you’ve made it when you get there? All of these questions become meaningful because I know in very general terms what you’re thinking of, namely, a place.

I could do something similar by asking you to think of something that happened to you recently, a true story with you as the protagonist. When did the event begin and end? Who was involved? Where did the events take place? What happened, i.e., what was the sequence of motion of fact, as Hemingway put it? How did it turn out and how did it make you feel? Why was it all necessary (what was the point)? These are all natural and reasonable questions that may be asked of any story. And, if I assume that you’ve followed my instructions, and thought of something that happened recently and to you, I can expect you to know the answers. Just as taking a mental look around a place you know well will prepare you to describe it in writing, so too will these basic questions (the so-called five Ws) prepare you to tell a story in writing.

And both of these skills are useful to you in your academic writing. You will often have to describe an organization or region or market in concrete terms, or just an ordinary social practice. Or you may need recount the recent (or ancient) history of the problem you’re studying, an unfolding series of current events, or the things you did to collect your data (i.e., you might be writing your methods sections). The ability to describe things and places, and to tell stories, will help you immensely in doing these perfectly “academic” things.

But I can’t just leave it there. There are more abstract entities you’ll need to be able to write about, more abstract ideas that you’ll need to be able reflect upon. With apologies to Hamlet for mixing his metaphors, you’ll need to learn to hold a mirror up to your mind’s eye and take a good close look at your concepts. (Interestingly, Senior sometimes suggests looking at your hand through a mirror too.) So I could ask you to imagine a theoretical object or a conceptual framework — an organizational hierarchy, for example, or a synthetic option, a collapse of sensemaking or a market equilibrium, a product innovation or a corporate merger. In all cases, I would ask you to pick something that you understand well if I was going to ask you to write about it. I’m not assigning reading homework, but writing homework, so we should begin with something you’re as familiar with as, yes, the back of your hand. If I’ve been invited into your classroom I can sometimes choose my examples by talking with your teacher, but if my examples turn out to be unhelpful (i.e., unfamiliar) then just ignore me and pick something that you actually have studied and do in fact understand well.

The important thing is to take this abstract object — essentially the concept without any particular thing in mind — and notice its parts. How are they related? Hierarchically, functionally, causally? Do the parts stand in relations of subordination to each other, or do they perform particular functions in concert with each other, or does one element cause effects in the other elements? Or is it a combination of these relationships? We have many different kinds of ideas about the objects that our theories are about. In fact, theories give us the conceptual resources we need to talk about those objects in very precise ways. Have a look at your resources every now and then and write about them.

I’ll write some posts next week about what I think you should be able to see. Remember Oliver Senior’s wise words: “the better drawing is not the more elaborate attempt to reproduce the visual appearance of its subject, but that which is the better informed.” That is, you’re not trying to reproduce what it says on the pages of your textbooks. You’re trying to write down what you learned from them, to write down what you know for the purpose of discussing it with other knowledgeable people. You are writing down your ideas as straightforwardly as you might draw a picture of your hand in a particular position. In fact, I’ll give Oliver Senior the last word:

The better draughtsman has more ‘on his mind’ concerning his subject; and by embodying his knowledge and understanding in each purposeful line or passage of his drawing, achieves with apparent — even with real — ease an expression of form, character, action — whatever may be his immediate object — that the novice, lacking such equipment and relying on his vision alone, finds beyond his power. (P. 8)