[See also: How to write a research project. How to write the background, theory, method, analysis and discussion sections. How to write the introduction and conclusion. How to review the literature and how to structure a research paper. How to finish on time and how to reference properly. Part of the Craft of Research series. Full program here.]

Imagine that you enter a parlor. You come late. When you arrive, others have long preceded you, and they are engaged in a heated discussion, a discussion too heated for them to pause and tell you exactly what it is about. In fact, the discussion had already begun long before any of them got there, so that no one present is qualified to retrace for you all the steps that had gone before. You listen for a while, until you decide that you have caught the tenor of the argument; then you put in your oar. Someone answers; you answer him; another comes to your defense; another aligns himself against you, to either the embarrassment or gratification of your opponent, depending upon the quality of your ally’s assistance. However, the discussion is interminable. The hour grows late, you must depart. And you do depart, with the discussion still vigorously in progress. (Kenneth Burke, The Philosophy of Literary Form, p. 110-111)

Modern research is embedded in an ongoing conversation among peers. Indeed, I define academic writing as the art of writing down what you know for the purpose of discussing it with other knowledgeable people. Your literature review is your effort to draw the outlines of that discussion, and to identify the participants to the conversation. (As Thomas Kuhn pointed out long ago, they are precisely the people that would have to change their mind in order for there to be a paradigm shift.) This also means that you are constructing an image of your reader, one who is not necessarily among the authors you encounter in your review, but who is familiar with the texts you find there. That is, you are conducting a reconnaissance of the territory that the conversation covers. You’re trying to find out what the conversation is about so that you can make a useful contribution to it. The literature review is the part of Burke’s “parlor” session where you “listen for a while,” trying to make sense of a conversation that was going on long before you got there. You should read the texts you find in that spirit.

It is a good idea to go into your literature search with some “exemplars” in mind. Your first objective should be to find some studies that are examples of the kind of work you would like to do in your own research project. Ideally, they will be framed by theories you are familiar with (and want to use this project to deepen your knowledge of) and supported by methods you understand (and want to develop your mastery of). If you don’t already have some published studies like this in mind, I encourage you to spend some time early in your project looking for them. They will usually not be studies of exactly the same object (a company, or product, or industry, or country, or market) that you have chosen, but they will be based on the sort of data you’re planning to collect, and apply some of the concepts that you have used to state your research question. If you have to choose between method or theory, I recommend finding studies that share your methodological sensibilities, the center of your iceberg. That is, you’re looking for examples of other researchers who have done the kind of research you’re planning to do. The better able you are to imagine what those researchers (the authors of the papers you find) were actually doing when they were collecting and analyzing their data, the more useful these papers will be to you. You want to feel like you’re part of the same community, and you want this feeling to grow as your research progresses already at the level of your literature review.

You only need two or three such examplars to begin with. They will provide you with a focus for the rest of your literature review. It is a good idea to find one relatively recent one, and one or two somewhat older ones. The reason for this will become clear as you begin to explore the “citation network” that surrounds them. Each paper will usually have a substantive bibliography, a reference list that cites the work that went before them. But they will also, hopefully, have been cited a few times by people who came after them. The examplars should indicate the extended “present” of your own research project, they should feel like your “contemporaries,” they should seem “modern” to you, like they are studies of the same world that you live in. The people who cite them, therefore, should be treating them as part of the current moment of an ongoing conversation. Reviewing the literature is a matter of gaining a good working understanding of what is being talked about in your discipline when your chosen topic is being discussed.

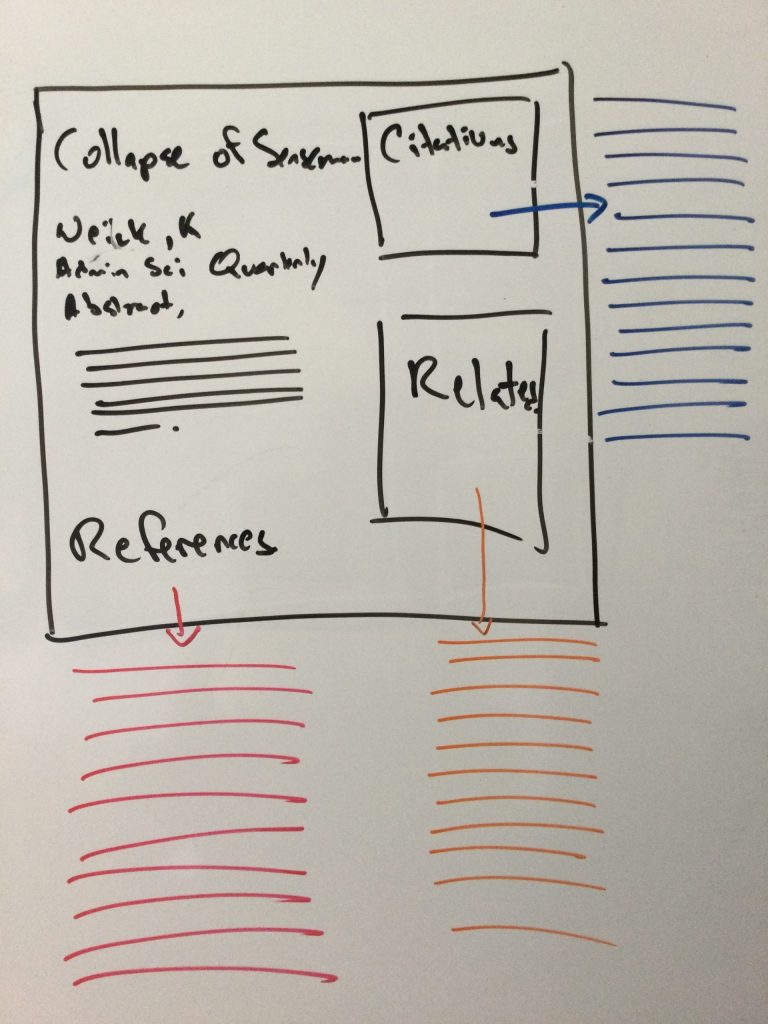

It can be useful to approach each paper using the entries in citation databases like Web of Science and Scopus as a model. Every article you read (black) will have references (red) in the past, and citations (blue) in the future. It will also have “related” articles (orange), which may be in the past or the future, and which may or may not cite the article directly. When reviewing the literature, you want to try to imagine the articles you read in this way, and you want to have the growing list of core articles with which you are familiar. Part of your familiarity with the literature is an awareness of the place of individual books and articles among other books and articles. As you proceed with the literature review, consider “color-coding” the papers you find. Some will be “black” in the sense that you have actually read them. Others will be be blue, red, or orange, in the sense that your awareness of them is still just at the level of whether they cite, are cited by, or related to the papers you have read.

This gives you a good, intuitive sense of the relevant standards of quality. Try to hold your search results to this standard. Assess papers on the way they actually present their results, rather than merely on where they’ve been published and how often they’ve been cited.

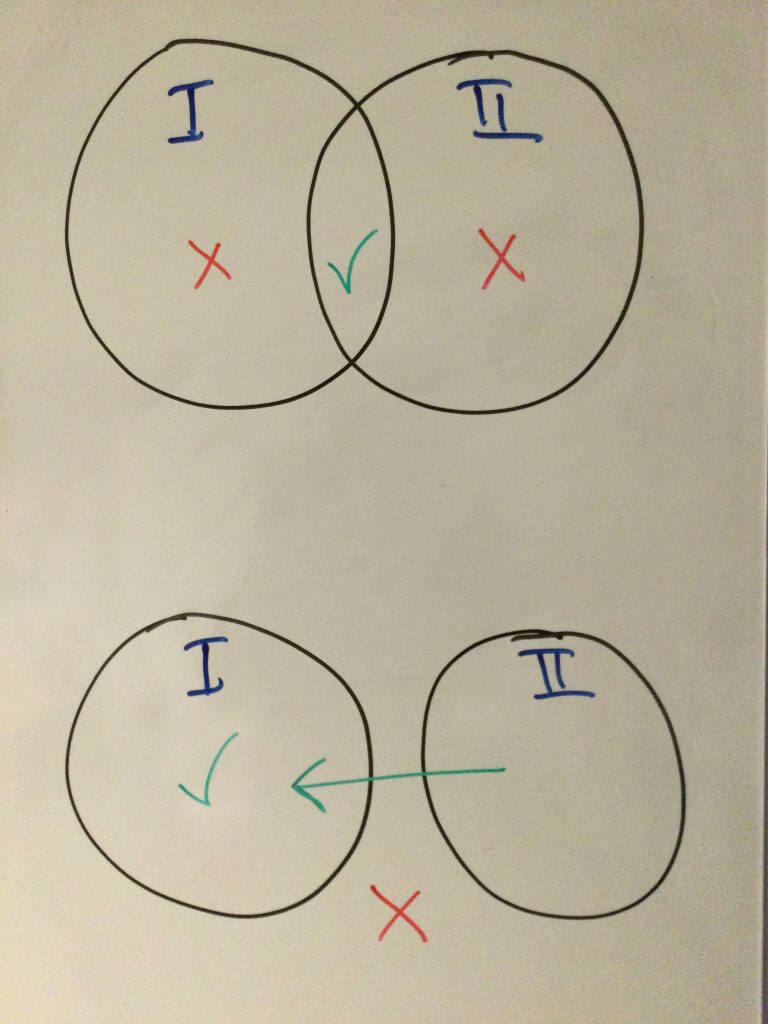

People often ask me about “multi-paradigmatic” or “interdisciplinary” research, which implies the difficulty of reviewing two or more literatures. My answer is always, albeit somewhat ironically (because I know I will be ignored), to recommend against it all together. Don’t make the problem harder than it has to be, I say; framing your study within a single well-established body of research is already difficult enough. But if for some reason you must, I recommend, first, looking for research that already brings the two literatures together (there’s usually someone who has at least suggested the need to this before) and then working from the center of this “inter-discipline”. That failing, I caution you not to situate yourself alone, outside either body. Choose one as your home discipline and then introduce the “other” to your “friends”.

I said to appreciate your finitude. Another way of putting this is to quote the Danish poet Henrik Nordbrandt: “Don’t overpopulate your hell.” The literature can sometimes appear overwhelming, like an ocean. Don’t think you have to exhaust it all in preparation for particular research project. Give yourself a certain amount of time to do the best you can. Once you’ve spent that time, accept that this will essentially be your frame of reference while you collect your data and carry out the analysis. Maybe a few articles will serendipitously cross your path in the later stages, but don’t spend any time looking for them. Address your reader as though this is the literature you share. Work from the center of your strength.

Finally, remember that “literature reviews” can be very boring to read if they’re just a summary of everything that’s been written on your topic. Instead, try to look for an unfolding story of the emergence of the compelling theory that your work will challenge and develop.

In the Q&A, responding to a question about using second hand sources, I mentioned Anne-Wil Harzing’s “Are our referencing errors undermining our scholarship and credibility?” It is very much recommended.

I also recommended Graff and Birkenstein’s They Say, I say, a very practical manual about how to position your work in the scholarly conversation.

For CBS students: check out the library’s page on information retrieval at my.cbs and our courses and events about literature searching.

Here are some posts on the subject:

“Never Write Literature Reviews”

“Ezra Zuckerman and the Literature”