Each of us knows a great deal. And there is a lot that we don’t know but is known by others. These are the things we learn by doing our literature review. Many researchers find this task daunting and, in this post, I want to try to summarize the advice I give to them.

Begin with a small set of papers that you have a close connection to. You may have authored or co-authored some of them yourself, or you may have worked closely with the people who have authored them. They may be written by members of your department or people who have collaborated with your colleagues. Ideally, you have met the authors of these papers and have a good understanding of the sort of research they do. You have a concrete image of where they work and how they go about their research, and you are, of course, at least moderately impressed with what they have accomplished…

(Note: If you are a student, you will not, of course, have such an intimate relationship with these papers. But you’ll recognize them because they have come up in your classes, and you’ll sometimes get the sense that your teachers are familiar with them in this way. They are central part of the discipline you are studying or, more precisely, the specialty that the class is focused on.)

When you read one of their papers, you can form clear images of the facts they represent and you have a well-grounded opinion of how likely their results are to be correct. You don’t have to be entirely convinced of their claims. But you do have to find them interesting, and you have to respect the research they have done. This list of papers can be quite short; even two or three can be sufficient, but I would suggest finding between six and twelve. Put them at the center of your search.

Locate them individually in the various databases that you have at your disposal. Here at CBS, at would recommend you find them in Business Source Complete, Web of Science, and Scopus.* Once you have found the articles, look at the bibliographical data that the database provides for them; notice that there is an abstract, some key words, a journal, and of course the authors. These are all going to be useful to you when you are looking for similar articles, since “similarity” here is just a reference to the data that the entries in the database share with other entries. Using your awareness of these similarities, you will be able to design searches that quickly and accurately locate literature that is relevant to your research.

But the entries, especially in Web of Science and Scopus, also let you think of each article as occupying a node in a network of citations. In addition to the bibliographical data, an entry usually contains the full bibliography of the article itself (its reference list, its list of sources, its “cited references”). It also links to a list of “citing documents”, i.e., all the articles in the database that have this article on their reference lists. Finally, they give you the option of searching for “related documents,” which is a long list of all the articles that share at least one reference with the article in question. (These can be organized by “relevance”, i.e., in order of how many references they share.) With this information, you able are able to position an article in the discourse to which it contributes.

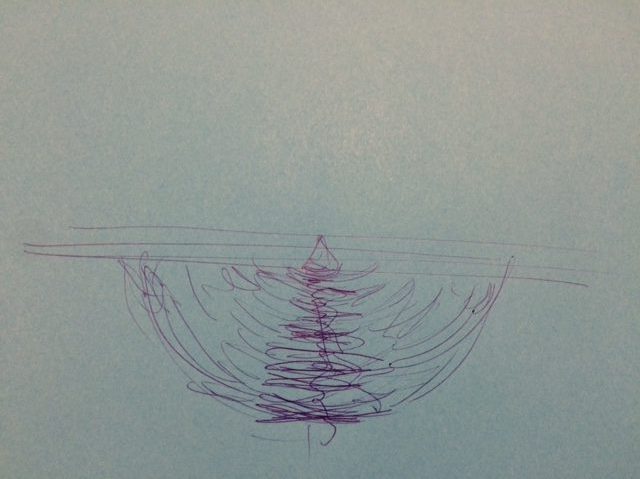

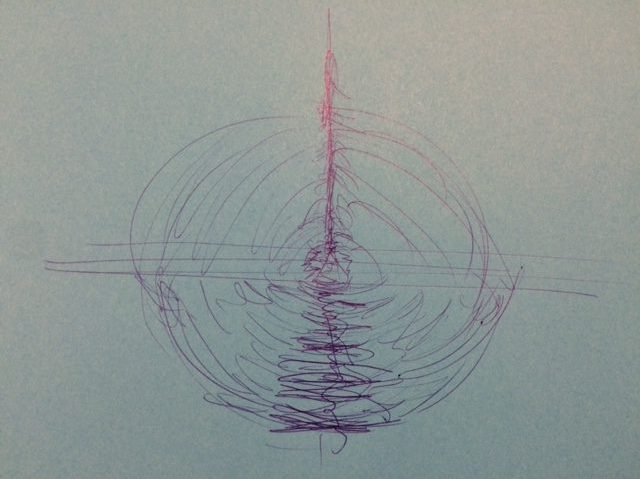

While a citation network may be large, it is not infinite. More importantly, it has a center and a periphery, as well as a past and a future. In the center is that short list of articles with which you are already very familiar and should be quite recently published. Behind them lie all their sources, which we can imagine as one long, shared bibliography; but, instead of putting it in alphabetical order, let’s arrange them by publication date, with the oldest at the furthest remove from your core papers. Also, let’s group them along a center line so that the papers that share references (or are otherwise topically related) are closest to each other, and those that don’t are further from the line. This will produce a sort “wake” trailing after the core articles and shading off into the “ocean” of published papers that are not directly cited but are nonetheless related to the articles you do cite. By a similar token, there will be papers that are contemporaneous with your core, and very relevant, but (since they were published at around the same time) will not cite your work (or that of your close colleagues). And there will be papers that are at quite a remove (either conceptually or bibliographically) from your core, but more or less related to the papers you cite, or the papers that are related to those you cite. An illustration might be useful:

But nothing is entirely static in research. The literature is constantly growing and it’s important to have a way of navigating on the ocean of scholarship. Obviously, your own research (and that of those core peers, whose research you are very familiar with and probably read about in draft and pre-print form) will follow a line proceeding from the (present) center of your research. Closely related to this line will be (future) papers that cite your core articles (albeit sometimes just in passing) and, again, the (future) papers that are related to those articles by way of shared references. We now get a diagram that looks a bit like this:

The key to all of this is to appreciate the finitude of the problem. While there is a lot to know, there are only a handful of very relevant articles, and a manageable amount of less relevant ones, before we finally reach your research horizon, beyond which you can safely remain ignorant of what goes on (until you get there yourself, of course). The ocean is a big place, but you’re only ever sailing in some local part of it. Don’t be afraid today of what is really just part of the adventure tomorrow. “Here be dragons,” is a myth born of ignorance. Uncharted waters are just places you haven’t yet explored.

____________

*Update: Patrick Dunleavy, whose views on writing and publishing are always worth taking seriously, has taken me to task on Twitter for this recommendation, calling it “outdated”: “Leaving out Google Scholar,” he argues, “‘costs’ your advisees. They’ll miss all grey literature (pretty vital in business studies on new topics), plus all books, book chapters & most conference papers.” Jo Jordan came to my defense: “But starting them on Google Scholar,” she countered, “condemns them to muddle and an inability to use IT to manage their databases. Need to see some total costings here.” I think that gets it mostly right and it reminded me of what Bill Evans says about keeping things “simple and real”. That’s the spirit in which I wrote this post. But I’ll have to write one specifically about Google Scholar at some point.