In a recent post, I tried to recover the role of imagination in George Orwell’s view of writing. “Probably it is better,” he said in “Politics and the English Language”, “to put off using words as long as possible and get one’s meaning as clear as one can through pictures and sensations.” What your writing finally represents, then, is not the state of things in the world, but your state of mind as regards those things. When Orwell said that your prose should be “like a window pane”, he didn’t mean a window on the world; he meant a window on your mind. Your writing can’t give the reader a direct view of the facts; but it can show the reader what you think the facts are. You can’t communicate the facts directly to the reader, but you can communicate your experience of those facts. You can tell the reader how you imagine the world to be.

Perhaps this is obvious but it bears restating. Indeed, I find it interesting that Orwell’s famous remark about “the first duty of intelligent men” sometimes being “the restatement of the obvious” comes from a 1939 review of a book by Bertrand Russell, who, in addition to being one of the great philosophers, was also Ludwig Wittgenstein’s mentor. In his introduction to the Tractatus, Russell aptly summarized the underlying (and ultimately too simple) assumption of Wittgenstein’s early work as follows: “The essential business of language is to assert and deny facts.” Wittgenstein’s book starts with the famous assertion (though he would say it’s not really an assertion of fact) that “The world is everything that is the case.” But my favorite line in that book comes a bit later on and brings us back to the imagination. “We make ourselves pictures of the facts.” It is this ability with which all good writing must begin.

Rereading Orwell’s review of Russell’s Power: A New Social Analysis, I was struck by how well it anticipates the themes of Nineteen Eighty-Four, and, perhaps a bit distressingly, the themes of 2018.

It is quite possible that we are descending into an age in which two and two will make five when the Leader says so. Mr. Russell points out that the huge system of organised lying upon which the dictators depend keeps their followers out of contact with reality and therefore tends to put them at a disadvantage as against those who know the facts. This is true so far as it goes, but it does not prove that the slave-society at which the dictators are aiming will be unstable. It is quite easy to imagine a state in which the ruling caste deceive their followers without deceiving themselves.

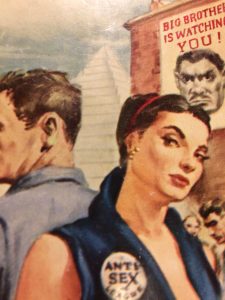

Let me emphasize that last sentence: “It is quite easy to imagine…” Ten years later, of course, he would publish the novel that demonstrated just how easy it is to imagine such a state, providing the referent for what we today simply call an “Orwellian nightmare”. We all have a pretty clear picture in our minds when we see those words.

As a counterpoint, I want to suggest a more pleasurable act of imagination. I want to suggest we take Orwell’s writing advice as a means to heed his political warning and propose that we “get [our] meaning as clear as [we] can through pictures and sensations” before we commit ourselves to the page. For years I’ve been telling people to decide at the end of the day what they will say during an appointed moment on the next. They often ask me how they should “prepare” themselves, and my sense is they are imagining a prodigious amount of reading, and note-taking, and pondering, and suffering in general. It sounds nightmarish to me and I always tell them that if they find it hard to decide what to write tomorrow they are doing it wrong. They should just pick one of the hundreds of things that they had a good understanding of already last week and express it in a simple declarative sentence. They should pick something that is “easy to imagine” today and then devote themselves to the very real difficulty of writing it down tomorrow. This “preparatory” act of imagination shouldn’t take more than ten minutes and it should be an entirely pleasant experience.

I honestly believe that this free, playful exercise of imagination is an essential bulwark against totalitarianism. It is what the dictators, if they exist, are trying to prevent. Let us call it Orwellian daydreaming.