There’s a famous story about Edgar Degas and Stéphane Mallarmé. Degas was trying to write poetry and wasn’t satisfied with the results. Since he had such great ideas, he couldn’t understand what he was doing wrong. “But my dear Degas,” exclaimed Mallarmé, “poems are made of words, not ideas!”

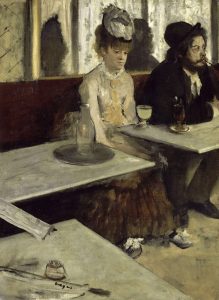

Like Degas, you may be suffering under the illusion that the trick to writing well is to have good ideas. To see why it may not be quite so easy, consider reversing the roles of the painter and the poet. Suppose Mallarmé had been trying to paint two people sitting in a café and was complaining to Degas about the difficulty. “I don’t understand it,” Mallarmé might say. “They’re right there in front of me. I see them so clearly. Why is this so hard?”

In the case of painting, we immediately understand why that’s not all there is to it. It’s not enough that you can see the scene you’re painting. Paintings are not made of images, but strokes.* Likewise, having an idea doesn’t in and of itself qualify you to write it down. You have to train your hands to do something quite specific.

But ideas are of course important. Indeed, learning to paint something does require you to learn how to see it, as painter friend of mine pointed out to me long ago. She sometimes wondered how people who say they can’t draw can even see. Learning how to write will likewise require you to think.

But this is really just a way of saying that writing improves our thinking, drawing improves our vision. Fortunately, just as Oliver Senior, when he was writing How to Draw Hands, was able to assume you have a model at the end of your arm to study, your writing instructor can assume that you have ideas in your head to write about. And not just any old ideas. Like Degas, I’m sure you’ve got some pretty good ones.

When you are practicing your writing, my advice is to focus on your better ideas. This is no different than looking at your own hand in a single position and in good light. Don’t try to draw a hand as it looks when you’re waving it around in the dark.

____________

*Update: I was talking to Jonathan Mayhew about this and he suggested an interesting variation. “Paintings (and drawings) are not made of images, they are made of shapes.” One might of course say paintings are made of strokes, drawings of lines. Poems are made of words, but perhaps also lines (in another sense) or even strophes. Essays are made of words, sentences or paragraphs depending on how you look at them. The important thing, however, is that when you’re trying to draw a face, you shouldn’t focus on the recognizably “facial” features. Rather, look at the ovals and rectangles and triangles and circles that the face in front of you is composed of, and then recompose those on the page. Whatever you do, don’t get lost in the details of the mouth or eyes or hair. Decompose the thing in front of you into its two-dimensional surfaces. Likewise, the seemingly brilliant ideas you have are composed of much less interesting, much less complicated, facets, namely, concepts and objects, and these can be rendered plainly in sentences. Indeed, they can be rendered simply by combining the right words in the right way, which is what Mallarmé was trying to tell Degas.