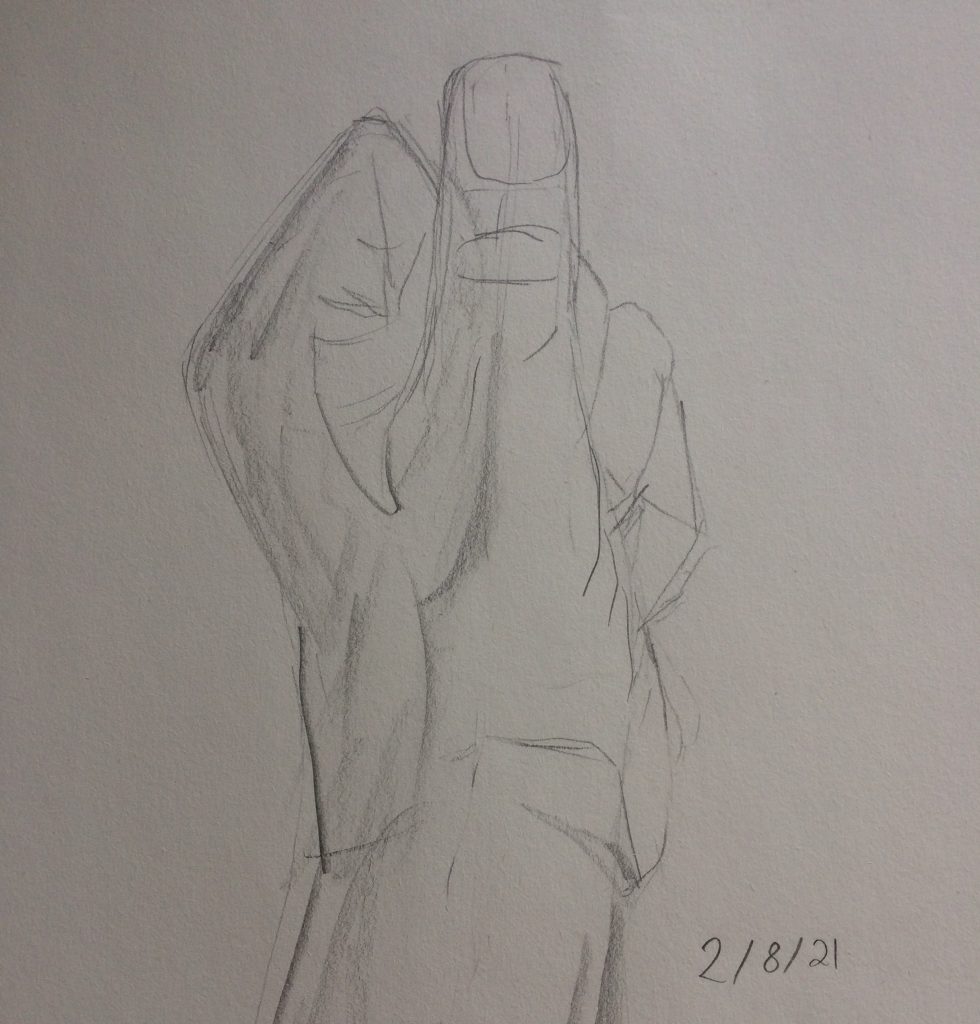

Look at your hand. Suppose I asked you to draw a picture of it. You would take out out a piece of paper and pencil and perhaps begin to draw its outline. Or you might have another way; you might begin with the play of light and shadow, or you might map out its surfaces. Notice that you’d be seeing the hand differently in each case and you’d be representing it according to this way of seeing. I don’t suppose you’re already doing this, so the last few sentences will have been acting mainly on your imagination. You may have actually looked at your hand but you have only imagined drawing it. Suppose I had said, “Look at your hand. Now, close your eyes. Imagine your hand.” What is the difference between drawing your hand and imagining it? What is the difference between imagining yourself drawing it and actually drawing it?

Notice that you can neither draw nor imagine your hand as such. You have to approach it as a fact first; you have to see it (imagine it) as a fact. Your hand can be open or closed, it can be relaxed or clenched, it can be palm-up or palm-down, it can be pointing or waving, it can be holding something or it can be empty. I can’t ask you to draw your whole hand in a single picture because a hand can only be seen from a certain point of view. Also, your hand consists of skin and muscle and bone and blood and nerves. You probably weren’t imagining drawing any of that when I asked to imagine drawing your hand. That is the difference between a thing and a fact. A thing (like your hand) can participate in any number of facts (like your closed fist or a wave or holding a pencil). When you imagine a fact you imagine a thing in a particular position, in a particular situation, in a particular arrangement of other things. In an important sense, facts just are the way we imagine things when they’re being something specific. Without the fact it is implicated in, your hand just “is”. Try to imagine that and you will fail. You can’t, said Kant, imagine a thing as such.

Long ago, Chester Barnard made an astute observation. If you take any particular organization, the amount of people who actively desire to be part of it is very small compared to the amount of people there are in the world. There are almost 8 billion people in the world. Only about 20,000 are students at the Copenhagen Business School. (In a strictly formal sense, Barnard would say the fact they study here proves that they are “willing” to do so.) There are probably some people in the world who would like to study here but don’t for one reason or another, but the number is a very tiny fraction of world’s population. The CBS student body is a “thing” (it would be better to call it a “population” of things, a bunch of people); all of humanity is another thing (another population). But it is a fact that there are about 20,000 students at CBS and another fact that there almost 8 billion people in the world. It’s hard to imagine “all of humanity” in any definite way. Even “CBS students” is a difficult thing to imagine. But the fact that some people are not studying at CBS, though they would if they could, is easier to get your mind around. It is a definite population with some definite characteristics. That also allows us to measure it. We can ask, How many of them are there?

One last thing about facts. We can get them wrong. If I say, “My hand!” or “CBS students!” or “Humanity!” I’m not saying anything I can be wrong about. I can form a vague picture in my mind that suggests, vaguely, what the words mean. But I’m not being specific enough to make a comparison with reality meaningful. These things merely exist … and, properly speaking, I’m not even claiming that they do. It is only by imagining something specific, about everything from my own hand, to an organization’s members, to the whole of humanity that the notion of “truth” gains any relevance. That’s what facts are for — for being right or wrong about — for knowing something about. But you really do have to imagine them first. Begin with your own hand. Imagine it. Picture it. Then move on to other people and the situations they find themselves in. Knowing something about them really just means being able to compare them to, yes, the back of your hand.