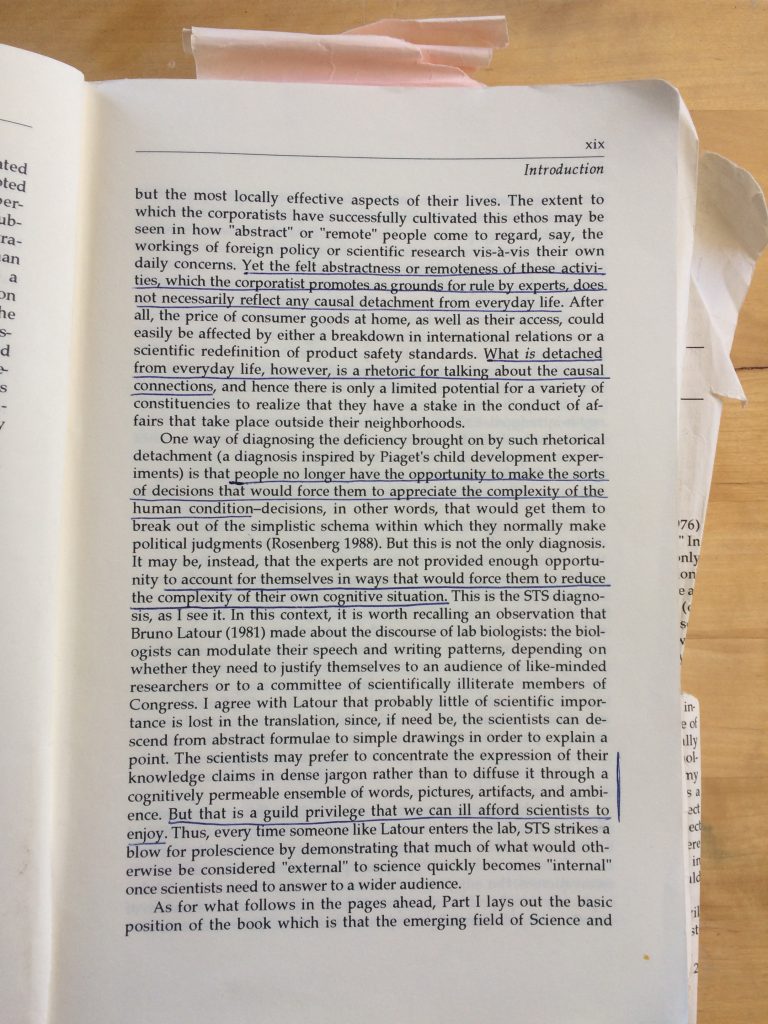

Thinking about the (fading?) hopes and habits of my craft, a thought occurred to me and I pulled my long-suffering copy of Steve Fuller’s Philosophy, Rhetoric, and the End of Knowledge off the shelf. As usual, it fell apart in my hands. I reassembled it and found that that the sentence I had remembered had been helpfully underlined by my younger self, probably twenty-five years ago. I don’t approve of that practice any longer (especially not using a pen!) but it was interesting to see how long these ideas have been with me.

“Scientists may prefer to concentrate the expression of their their knowledge claims in dense jargon rather than diffuse it through a cognitively permeable ensemble of words, pictures, artifacts, and ambience,” Steve tells us. “But that is a guild privilege that we can ill afford scientists to enjoy” (1993, p. xix). It was that last sentence I was looking for. I wanted to connect it to what turned out to be another underlined sentence in that book, which I have talked about before on this blog: “Truth and falsehood are properties of sentences in a language that has been designed to represent reality; prior to the construction of such a language, there is neither truth nor falsehood” (p. 189). Representation is difficult, and the difficulty, Steve tells us, is rhetorical. We have to “beat the logical positivists at their own game by envisaging what it would be like to implement their account of language.”

When I was 25, that’s what I thought I’d be doing when I grew up. And, in a way, that is exactly what happened. I am implementing language.

Scientists, researchers, scholars, academics … whatever we choose to call them … are using language to represent reality. Now, you might argue that everyone does this. “The essential business of language,” as Bertrand Russell put it, “is to assert and deny facts.” But a moment’s reflection should remind us that not everyone is trying so very hard to do this very well. Ordinarily, we don’t care very deeply about the facts. “In everyday life,” Steve reminds us, “an utterance is presumed to move its audience unless explicitly challenged.” We don’t usually use language to present our understanding of the facts with the intention of letting them correct us if we’re wrong. Ordinarily, we’re telling people how we feel about them and how we think they should feel about us. We’re telling them what to do, not what we’ve got on our minds. Represent reality? We pay people to do that! Scientists, researchers, scholars, academics …

“Ordinary language,” says Steve, “is ill suited to any of the usual philosophical conceptions of epistemic progress” (p. 187). But academic writers are no ordinary language users! We expect them to make progress in the usual, philosophical way, don’t we? We expect them to discover the truth and represent it. We want there to be people who know what the facts are and who can explain them. But must they be able to explain them to us? If ordinary language is “ill suited” to representation, why can we “ill afford” to let scientists use their jargons among themselves? Why must they paint us pictures too?

For Steve, it’s all about what in fact happens when a scientific claim is challenged. Scientists “will often justify it,” he says, “by invoking standards that, indeed would test the validity of the utterance if construed representationally, but which, under normal circumstances simply serve to terminate the discussion” (p. 189). Scientist who are challenged in public are likely to make hand-waving gestures at the complexity of the underlying data that supports their claims and, sometimes, even start browbeating skeptical objectors as “science deniers”. Sometimes they will invoke the intricate and expensive laboratory equipment that they use in their work, sometimes they will invoke the “vast peer-reviewed literature” that, effectively, insulates their own contributions from criticisms. “This institutional arrangement,” Steve reminds us, “is rather expensive to maintain,” but it is necessary if the the language is to afford us “representation” and “reference” (p. 188). All too often, unfortunately, this system of reference becomes a system of deference — a signal that continuing a critical line of questioning will simply cost too much.

“The search for truth is quite an artificial inquiry,” Steve admits, and “one that is directly tied to the regimentation of linguistic practices.” Those practices, in turn, are tied to “surveillance operations” that allow us to test the truth and falsity of utterances. But, to repeat, those operations, in part because they’re so expensive, are more often invoked than deployed, which brings about a slide from “the representational function of language” to the “rhetorical function of representation”; and here Steve makes a point that he couldn’t have understood the signifiance of back in 1993: “A common example of this representationalist rhetoric occurs whenever one scientist incorporates another’s results into her own research without feeling a need to reproduce the original study.” This was once a commonplace, but the replication crisis gives it scope!

These days, the problem isn’t that scientists are unwilling to abandon their “dense jargon” in favor of “a cognitively permeable ensemble of words, pictures, artifacts, and ambience.” In fact, the poster child of the replication crisis is still the second most watched TED talk of all time. Scientists are happy to make their work available for mass consumption as “ideas worth spreading”, long before they’ve let their peers approach them as theories worth testing. By the time somebody does apply a “verificationist semantics”, it’s often too late. Perhaps it is time to to return to a more “artisanal” sensibility? What we can’t afford is to let scientists circulate their representations only in the cognitively hospitable environment of the mass media, where their truth is more often presumed than challenged. We need to let them hold each other to their higher standards, their more expensive tastes. Like other guilds, we need them to regulate themselves.

This discussion reminds me of the idea that lots of people don’t seem so sensitive to the truth value of their statements. I think it’s common in writing for people to write or read based on how something sounds rather than its literal meaning. Listening to the music rather than the words, as it were.

One example we’ve discussed in the past is the final sentence from the “power pose” paper: “That a person can, by assuming two simple 1-min poses, embody power and instantly become more powerful has real-world, actionable implications.” This article was later disowned by its first author because of various problems with measurement and data analysis, but, even beyond all those issues, that sentence never made sense: it was never supported even by the claims in the paper. I think this happens with a lot of science (and other) writing, that people write sentences with a good cadence and a message that is vaguely consistent with the authors’ views, and then readers don’t notice because they’re not reading these sentences at a literal level.

Thanks for this, Andrew. I think it’s an important point. It’s hard to know what to do about it. I’m going to go back and read Heidegger on “idle talk” (Being and Time, §35). As I recall, he urges us to accept it as a part of our everyday existence, our “being there with others”. That’s why I focus on those “institutional arrangements” that are supposed to lead us back to our grounding in reality, facts, truth. Being a scientist isn’t just another ordinary social activity.

“Yet the obviousness and self-assurance of the average ways in which things have been interpreted, are such that while the particular Dasein drifts along towards an ever-increasing groundlessness as it floats, the uncanniness of this floating remains hidden from it under their protecting shelter.” (H. 170)