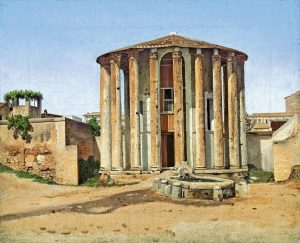

Source: WikiArt.

Over the last two posts, I’ve been defending the very idea of the five-paragraph essay. I have been reacting mainly to Dana Ferris’s critique of an assignment I proposed for discussion: write a five-paragraph essay that explains how to find a thing or place you think your classmates would find interesting. Ferris is not convinced that this exercise is sufficiently meaningful and, more worryingly, thinks that it makes unfair assumptions about the reader’s awareness of interesting places and things. But her main issue is with the imposition of form. While Nigel Caplan shares Ferris’s skepticism about telling students to observe a strict five-paragraph structure, he grants that “paragraphs are important” and, most hopefully, sees some value in my suggestion to limit the task in time. “Your 27 minute advice is interesting,” he says, “but no more a rule than any other advice about writing.” That’s what I want to get into in this post.

I should begin by being upfront that I don’t consider those 27 minutes mere “advice”. I do, in fact, present it as a rule, albeit one that writers are free to appropriate in their own way in their own process. If they want to write 18-minute paragraphs and that works for them, I’m not going to tell them they are wrong. What I do tell students is that they will not regret having the ability to write down anything they know in coherent prose paragraphs 27 minutes at a time and that if they want to develop that ability they might try following my rules for a few weeks. At the end of the day, it’s going to be self-discipline that gets it done, but they are (willingly) subjecting themselves, properly speaking, to rules. Once they’re committed to the process, that is, they’re either following the rules or not, and there isn’t much ambiguity about it. Hopefully, they’ll see them like the rules of a game, i.e., a set of constraints that makes an activity interesting and even fun. And sometimes, of course, my approach affords writers the thrill of breaking rules.

The other thing I tell them is that writing paragraphs 27 minutes at a time is something I know, not only how to do, but how to help people get better at. If they are trying to produce paragraphs by some other means, I’m not certain I can help them because I’m less clear about what they’re actually doing when they are writing. The constraints that I put on the assignment gives us a clearly defined problem to think about together. The student will have decided in advance what they want to say, they will know who their reader is and, preferably, what it is about the key sentence that this reader will find difficult (so difficult that a paragraph is needed). The time constraint itself lets the conversation be about their actual real-time writing ability. If the student and I agree that the text we’re looking at was produced with a measured amount of effort, then my criticism of that text can go directly into becoming more effective under similar conditions next time. I’m not telling the student what’s wrong with their text; I’m telling them what they can do better.

I call this “the writing moment”. The trick is to get writers to appreciate their strong position of advantage with respect to the reader. (For those who have seen The Matrix, feel free to imagine yourself as the One, working in Bullet Time.) A paragraph takes about a minute to read and, if your prose is in good shape, about half an hour to write. Your job as a writer is to spend 27 minutes arranging a single minute of your reader’s attention. You can presume that the reader will do exactly what they’re told, namely, pass one word after another through their consciousness in the order you’ve determined. That’s the only thing the reader is letting you do to them, but the reader is, by definition, submitting fully to your instructions: this word, then this one, then this next one. It’s true that you can lose your reader or cause them so much discomfort that they have to stop, but that, too, is part of the problem the writer is addressing in the moment of writing. The ability to write a good paragraph is simply the ability to make good use of one minute of your reader’s time.

With this in mind, it also becomes easier to defend assigning exactly five paragraphs. It lets you tell your students you expect them to spend, well, exactly two and half hours actually writing the essay (and maybe another half hour copy-editing). You can tell them you don’t want them to suffer all night or the whole weekend. You just want them to make some decisions about what they want to say, and then give themselves five 27-minute writing slots to get it done. You can then look at the results and see what needs work, what skills they need to develop. More importantly, when thinking about the text as a whole, students can be asked to imagine five-minutes of their reader’s attention. Like I said to Ferris on Twitter, it’s just a way of giving the the student a concrete sense of the limits of their reader’s patience. You have to come up with a topic that is worth five minutes of the reader’s time to hear about. In the case of the assignment we’ve been discussing, it’s a question of choosing a place or a thing that’s hard enough to find (and still worth finding). The paragraph constraint, then, serves as guide for selecting your content. It cultivates a sense of the student’s materials.

While thinking about this I’ve been reading William McNeill’s The Time of Life: Heidegger and Ēthos (2006). It’s a difficult book about a difficult subject, and I probably can’t do either Heidegger or McNeill justice in my humble writing instruction. Nor do I think students have to become proper existentialists in order to write well. (Indeed, I’m not as comfortable as, say, John Warner insisting that students even be “authentic” when they write at college. But that’s for another time.) Still, I like the idea of thinking of writing as a kind of “dwelling” and of teaching students to “apportion” their “composure”, one paragraph, one moment, at a time. Writing an essay involves the composition and arrangement of paragraphs that correspond to a series of experiences in the mind of the reader. There’s an “ethics” to it, certainly an ethos. Like “being good”, writing well means “finding ourselves correctly attuned in the apportionment of the moment” (McNeill, p. 89, quoting Heidegger’s course on Aristotle’s Rhetoric). Our students need to learn how to establish a moment of composure and make deliberate use of it. The five-paragraph essay, then, when used properly, provides a great occasion on which to dwell on the essence of composition — to appreciate our finitude.