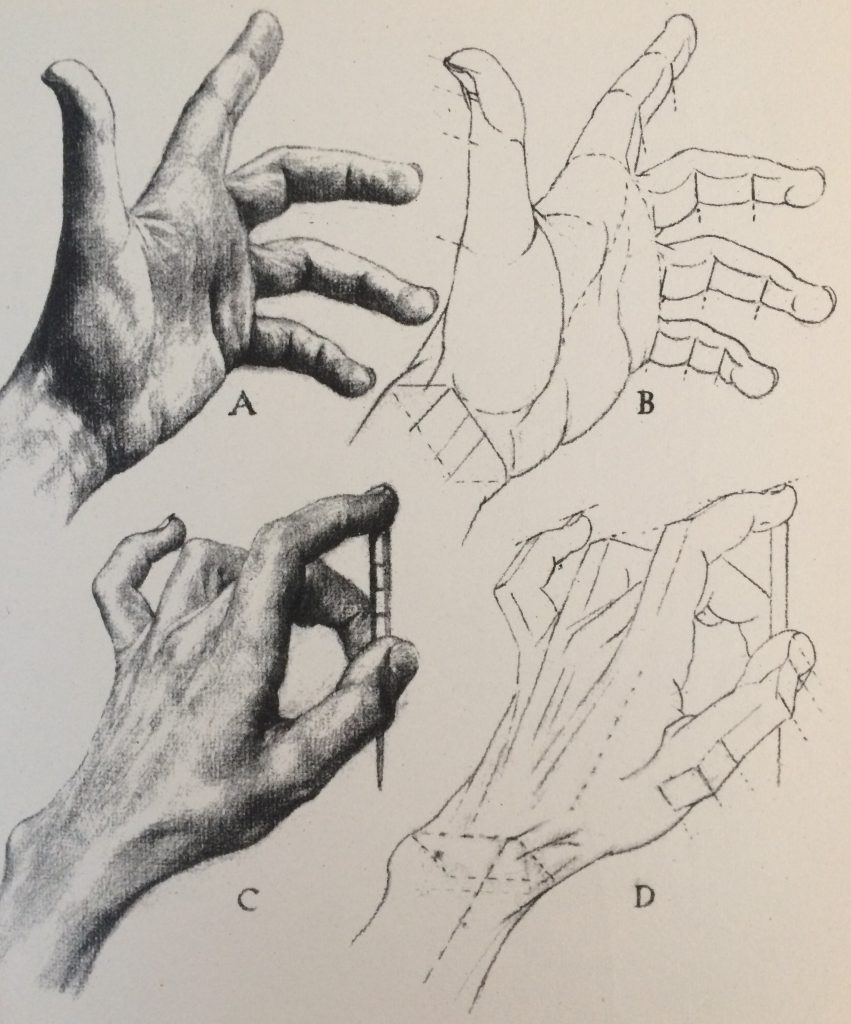

“…the difficulty encountered by the student is that of representation by drawing of a familiar yet highly complex piece of physical mechanism…”

Oliver Senior, How to Draw Hands

I suspect that one source of the animosity that some writing instructors feel towards the five-paragraph essay is a failure to appreciate the complexity and variety of individual paragraphs. But we should remember that telling students to “write a paragraph” is almost as open a task as telling them to “use their hands”. Indeed, I often compare the task of writing a paragraph about something they know to the task of looking at their own hand and drawing it. Notice I didn’t tell them what they had to know, nor did I tell them what position to hold their hand in. But what if I had? “Write a paragraph about your opinion of the Prime Minister.” “Draw a picture of your fist clenched in anger.” Even when the content is specified, the possibilities are endless. We are making some reasonable assumptions about the student’s mind and body, which may sometimes need to be modified to accommodate exceptional cases. (Not all students have a Prime Minister to opine about; not all students have a fist to clench in anger.) The student is now free to solve the problem in a manner that demonstrates the competence we are (obviously) testing.

The first thing the student must do is to specify the object. The student no doubt has many different and perhaps contradictory opinions about their head of state. Since the task is to write a single paragraph, some decisions have to be made. Will the student concentrate on the substance or the style of the leader? Will the student choose a single idea to present unequivocally or will the student declare their ambivalence? Likewise, the student’s fist can be observed from many different vantage points. Will the student represent it from their own point of view or from the point of view of an observer? Will the observer be the person toward whom the anger is directed? Will the fist be shaking in the air or pounding a table? Again, there are many different ways of solving the problem. An idea, like a hand, is a complex object.

The next thing to consider is the reader, the viewer. What assumptions does the receiver bring to the experience of the representation? When writing, I always present this as “the difficulty” that the reader faces when confronted with your idea. Will the reader find it hard to believe, hard to understand, or hard to agree with? You may think your prime minister is an inspiring leader or a mass murderer. What does your reader think? What is hard about the claim you are making? What resources does your viewer bring to your drawing of your fist? What symbolism are they capable of discerning in it? What will they make of the cufflinks you include in the drawing? What will they make of the ring on your finger? What will they make of the hair, the wrinkles, the tattoo? All of these are questions that need to be considered when solving the problem of expressing anger through the representation of a hand.

Finally, there’s the question of time. How much time to do you have to produce the drawing or the paragraph? And, given that, how many attempts will you be able to make? If this is an external constraint, the question can influence the decisions you make about the content and audience. If you are free to decide yourself how much time to put into it, you will obviously take the result of those earlier reflections into this one. I won’t pretend to know anything about drawing, but when it comes to writing I recommend working in 18- or 27-minute sessions separated by 2 or 3 minute breaks. That’s a good amount of time to get a paragraph down. You can make two or three attempts an hour that way, and if your aim is to improve your writing, it’s a good idea to practice. So if you’re trying to improve your students’ writing, I likewise encourage you to get them to write in this way. Get them to appreciate the finitude of their problem. If possible, get them to enjoy it.

A paragraph, like a hand, is a highly complex mechanism. But it’s also a very familiar one. I consider the paragraph to be the “unit of composition”; John Warner prefers to think of the “idea” as the unit. Our important point of agreement is that this focus of our attention should become familiar to the student. Writing a paragraph should be as ordinary an experience as having an idea. Writing a good paragraph should be a bit more rare, but students will also have significantly fewer good ideas than ideas in total. And this sense of quality in writing and thinking is much like our sense of quality in drawing and seeing. The good writer is better able to think something through; the good draftsman is better able to see the aspects of things. The craft of representing improves the precision of our experiences. What is really happening is that we are coming to appreciate the complexity of the “mechanism”, what Kant might call the manifold of experience through which we come to know the objects among which we live. Overcoming the difficulty of representation is a matter of becoming familiar with complexities.