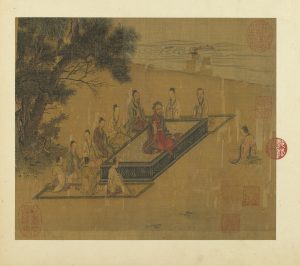

Confucius’s classic text The Great Learning begins like this:

The great learning takes root in clarifying the way wherein the intelligence increases through the process of looking straight into one’s own heart and acting on the results; it is rooted in watching with affection the way people grow; it is rooted in coming to rest, being at ease in perfect equity.

This is Ezra Pound’s translation—he calls it The Great Digest or Adult Study. Reading the passage, I realize that this really does express my philosophy, and especially what I try to accomplish when helping people to improve their writing. Writing is very much part of the process of adult study.

I agree with Pound/Kung that intelligence can be increased through a disciplined process. “Looking straight into one’s own heart and acting on the results,” is of course a way of improving your whole intelligence. An important step is to develop “precise verbal definitions of [your] inarticulate thoughts”; Pound simply calls this “sincerity”, i.e., to be able to say plainly and straightforwardly what you think. When you think about it, it is easy to see how such frankness can improve your intelligence and, I hope, just as easy to see how insincerity might hinder or even counter such development.

Universities ought to be places where the frank expression of thought is encouraged and protected. They should also be places where “the way people grow” is “watched with affection”. I have had the pleasure of watching people grow over the past fifteen years. But I have mainly been working with early-career researchers and PhD students. Or rather, it is mainly when working with them that I have the privilege of watching people grow. As undergraduate programs grow and are made more cost-effective, the contact between student and teacher offers little opportunity for such careful observation. I think this is a loss to the teacher as well as the student.

Notice that, according to Kung, your learning is rooted in watching how others grow. One of the functions of students on a university campus is to provide teachers with this important experience. Interestingly, some translations of Kung reduce Pound’s (perhaps overly interpretative) phrase to the claim that the aim of the Great Learning is “to renovate the people”. This top-down attitude seems to be more common today. Certainly, programs are organized in ways that leave little room for teachers to appreciate how their students’ minds are growing more articulate. This is due in part to a number of unproductive misconceptions about the role of writing in education. I’ll say more about this next week; for now I just want to emphasize that writing should have a much more prominent place in higher education than it does today. Less talk. More text, I say.

We should not forget the need to come to rest, to achieve a balance. Intelligence grows naturally if we think about things (and articulate our thoughts) in an orderly way. The process can’t be forced but it can be supported. It can also be interrupted, confounded, and sabotaged. Scholars have an interest in finding ways “to rest in the highest excellence,” as other translations put it. It is their job, in a sense, to “grasp the azure”.

(Note: This is a lightly updated post from my retired blog. I linked to it also in a previous post here about what sorts of assignments might afford opportunities to watch our students grow.)