Well it's a nice idea. No one told Deleuze and Guattari, though.

— Ella Taylor-Smith (@EllaTasm) March 20, 2018

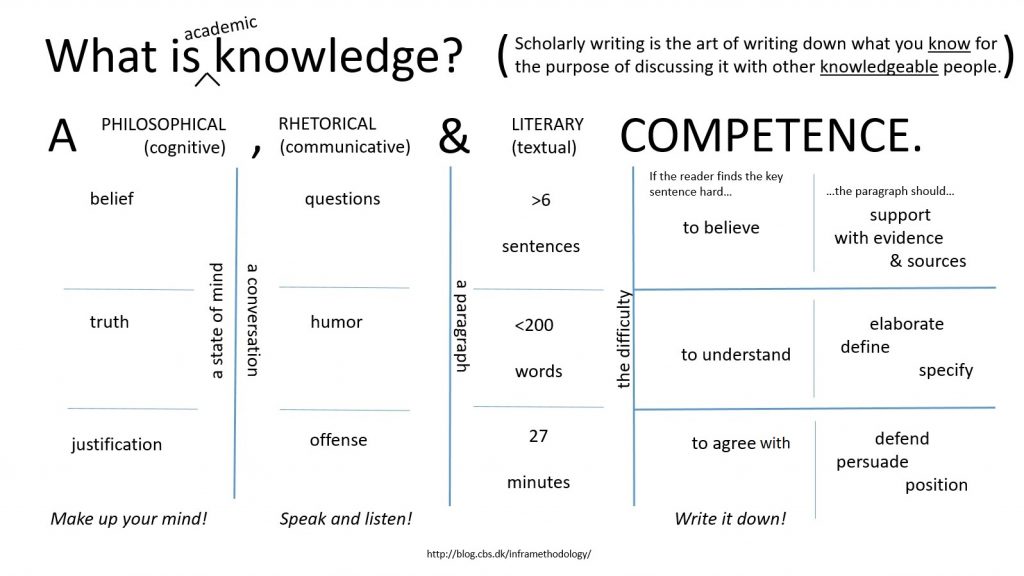

I get this quite a lot, actually. Sometimes (as I think it’s intended here) it is a (good-natured) complaint about Deleuze and Guattari; more often it’s an attempt to make me look silly. Other writers have been invoked to this end — Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Wittgenstein — almost always with the insinuation that I would ban their books, or that I am at least somehow offended by them. If my rules were universally followed, it is said, none of these great thinkers would ever have written their books. Kierkegaard himself can be said to have ridiculed my position in advance, calling me out, a century before my birth, as an “enterprising abstracter, a gobbler of paragraphs … who will cut [thought] up into paragraphs … with the same inflexibility as the man who, in order to serve the science of punctuation, divided his discourse by counting out the words, fifty words to a period and thirty-five to a semicolon.” (Ouch, says the writing coach who defines the paragraph as at least six sentences and at most 200 words to be written in exactly 27 minutes, and strung together, forty paragraphs to a paper.) Surely writing is not solely about supporting, elaborating or defending statements of fact, they balk. Surely there’s something more interesting going on.

In my defense, I wouldn’t burn any of their books. Their existence doesn’t offend me in the least; my life is the richer for it. Indeed, I’d object to burning them in the strongest possible terms. It’s just that, as I usually put it when talking to students, I don’t know how they were written. I can’t help you write something like them. “There is no difference,” say Deleuze and Guattari, “between what a book talks about and how it is made.” And for the longest time I’ve been happy to admit that, half the time at least, I don’t know what they are talking about. But Ella’s tweet reminded me of one paragraph that did once offend me, albeit in a way that might surprise you.

I was younger then and very much on the same page as Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, Deleuze and Guattari. Like Foucault, I was happy to leave the order of things to the bureaucrats and the police and write out of the unruly chaos of my own damnable heart. But then I got to the “War Machine” in A Thousand Plateaus and read this shockingly conventional, altogether orderly paragraph:

Georges Dumézil, in his definitive analyses of Indo-European mythology, has shown that political sovereignty, or domination, has two heads: the magician-king and the jurist-priest. Rex and flamen, raj and Brahman, Romulus and Numa, Varuna and Mitra, the despot and the legislator, the binder and the organiser. Undoubtedly, these two poles stand in opposition term by term, as the obscure and the clear, the violent and the calm, the quick and the weighty, the fearsome and the regulated, the “bond” and the “pact,” etc. But their opposition is only relative; they function as a pair, in alternation, as though they expressed a division of the One or constituted in themselves a sovereign unity. “At once antithetical and complementary, necessary to one another and consequently without hostility, lacking a mythology of conflict: a specification on any one level automatically calls forth a homologous specification on another. The two together exhaust the field of the function.” They are the principal elements of a State apparatus that proceeds by a One-Two, distributes binary distinctions, and forms a milieu of interiority. It is a double articulation that makes the State apparatus into a stratum. (ATP, p. 351-2)

What was I to make of these “definitive” analyses, this “undoubtable” polarity? Were Deleuze and Guattari expecting me to take this straight? Was my ass no longer a wolf? Two heads? Why not a thousand? Why not a multiplicity? And who was this Dumézil guy, anyway; wasn’t he some sort of fascist? Why quote him and not Henry Miller? What gives him this privileged position from which to speak? You get the idea. You’ve probably been there at one time or another yourself. But today, when I recalled this paragraph to my mind, I suspected something and took a closer look.

It consists of 8 sentences and 189 words. It says one thing, viz., “political sovereignty, or domination, has two heads: the magician-king and the jurist-priest,” and elaborates on it. Arguably, it also supports it, but it does so on the authority of Dumézil, which it endorses as “definitive”. It can be said to be an elaboration of Dumézil, except that he did not talk about the “State apparatus.” The key sentence might in fact be better said to be the last one: “[The opposition of magician-king and jurist-priest] is a double articulation that makes the State apparatus into a stratum.” After reading this paragraph, I dare say, we’re in no doubt about how it was made and we know, more or less, what they are talking about. It lays out the simple reasons behind a complex claim. It clearly exposes them to the criticism of their peers.

That is, maybe Ella is wrong. Maybe someone did tell Deleuze and Guattari what paragraphs are for and how they work. (Perhaps Deleuze’s teachers at the Lycée Carnot?) Indeed, maybe they made their books altogether deliberately out of paragraphs. “Each morning we would wake up, and each of us would ask himself what plateau he was going to tackle, writing five lines here, ten there.” They took their title concept “plateau” from Gregory Bateson, describing it as “a self-vibrating region of intensities whose development avoids any orientation toward a culmination point or external end”. Isn’t this how I advise authors to approach a moment in which to write a paragraph? I think it is.

Even Deleuze and Guattari’s translator seems to have missed this point.* Brian Massumi tells us that A Thousand Plateaus “presents itself as a network of ‘plateaus’ that are precisely dated but can be read in any order” (ix). But it’s the chapters, not the paragraphs, that are dated in this book. Perhaps he was misled by what the authors themselves say: “a book composed of chapters has culmination and termination points. What takes place in a book composed instead of plateaus that communicate with one another across microfissures, as in a brain?” (ATP, p. 22, my emphasis) The word “instead” leads us naturally to think that what looks like chapters are really plateaus. But the point is that the book was not composed into chapters, nor even around those precise dates, the moment when what is being talked about (how it is made) existed in some “pure form,” as Massumi suggests. Actually, forget the philosophical argument and just do the math: there are fifteen chapters in the book. But there are about 500 pages and an average of two paragraphs to the page is not a bad guess. What there’s a thousand of is neither chapters nor sections but paragraphs. Every morning the authors would get up and make one here, another one there. That’s what it’s about.

__________

*The idea that “chapters” = “plateaus” in A Thousand Plateaus seems to be pretty standard. It’s also how Brian Adkins approaches them in his critical guide (pp. 15-7).