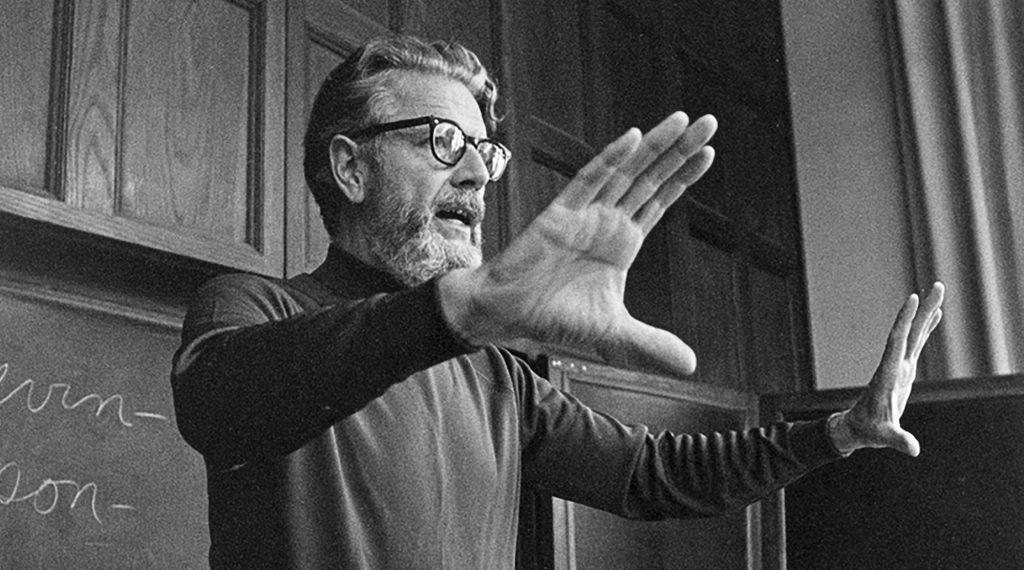

[Note: this post is part of a series on the “substance of the craft” of scholarly writing. Inspired by by Wayne Booth (co-author of The Craft of Research) and Oliver Senior (author of How to Draw Hands), I argue that composition is the coordination of words and ideas, paragraphs and propositions, sentences and the state of things.]

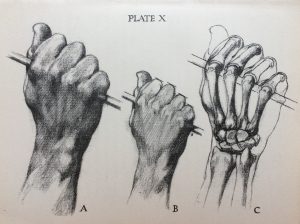

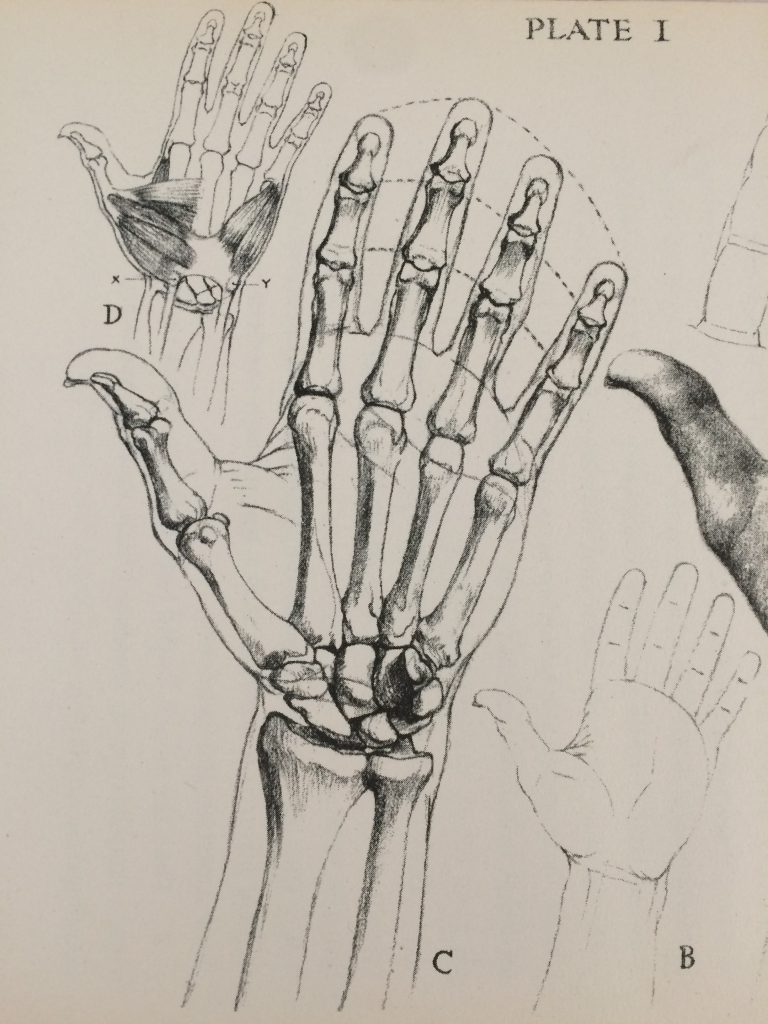

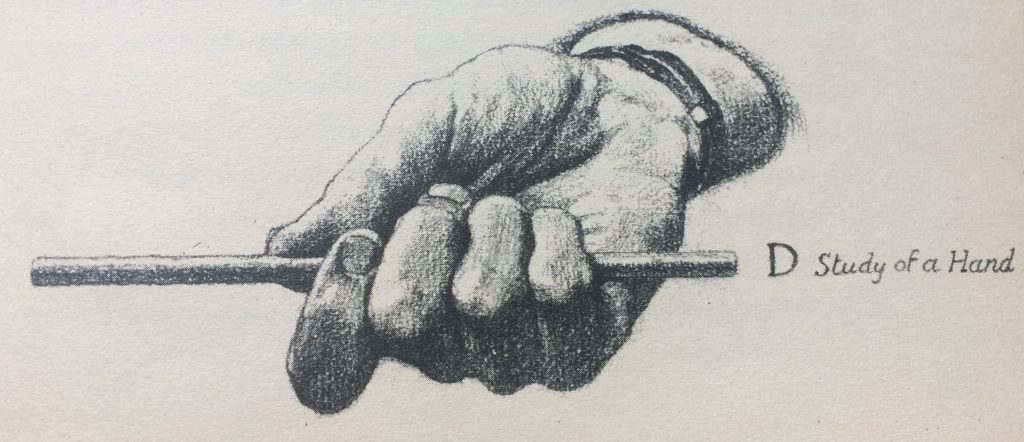

A drawing reveals an understanding of the subject. Different artists understand their subjects differently, as can be seen by comparing Oliver Senior’s understanding of his own knuckles to Paul Cézanne’s understanding of Ambroise Vollard’s. There is no question that both are capable artists, but they obviously had, as Senior might have put it, different things “on their mind” when they were rendering the hand they were looking at. Senior helpfully includes his understanding of the skeletal structure of his hand (though he is careful to remind us that those are not his bones). But his aim was also more didactic than Cézanne’s, and we must remember that Vollard’s hand is but a detail in a full portrait, whereas Senior’s emphasis is very definitely on the hand itself, alone. Both artists, in any case, are trying to show us what they see.

I hope you will agree with me that Cézanne’s hand, while less detailed than Senior’s, is just as as well-informed (to use Senior’s language). It serves its purpose in the portrait but it doesn’t cut corners; it is “true” to human anatomy; it is an entirely possible hand in an altogether plausible position. Cézanne has not sidestepped the difficulty of drawing a hand by replacing it with a mere symbol — a bent fork or a bunch of bananas, for example. If he had, we might still understand that Vollard is holding a book in his hand, but we would not get the same overall sense of his humanity. It would be getting the facts right, but it wouldn’t feel right. In fact, the detail that I’ve cut off from its context for this post might not make any sense at all on its own if it wasn’t so well drawn. We might literally mistake it for a fork if we didn’t see it at the end of an arm. Somehow, however, using only a few simple brushstrokes, Cézanne gives us a flesh and blood (and, yes, even bone) human hand. It’s worth appreciating that accomplishment.

Now consider the sentences in your paragraphs. Think of a sentence in a paragraph describing a larger fact, or a sentence in a paragraph that is presenting the conceptual model you have built to guide your analysis of your data. You know the overall picture and you know how the parts fit together. That is, you know what you are talking about because you have studied it carefully. But do you know how to render each detail so that it conforms also to the underlying, unseen structures that constrain reality, the actual and possible state of things? If you read the sentences separately, out of context, do they still convey something? Do they feel true to the facts or the models you are writing about? Obviously, they won’t capture the full meaning of what you are trying to say in the paragraph. But are they utterly dependent on the context to mean anything at all?

Academic writing is a highly contextual and conventional affair. We often rely on our readers to play along with our use of technical jargon to communicate our ideas. It’s a bit like the nervous tick of saying, “you know,” after every sentence in conversation. We keep asking our reader to do the work of putting the image together because we know we’re not doing a very good job of explaining it ourselves. It’s not there on the page as the modernists used to say, even if it is somehow available in the discourse between us. More often, however, the reader doesn’t do the work we hope they will. Instead they simply let us get away with being vague, leaving them none the wiser about what we really mean, but happy to grant that we know our stuff. We have persuaded them that we’re smart (and we probably are) but we have not actually communicated our ideas to them. We have certainly not opened ourselves to criticism from our peers.

I am trying to persuade you to work on your sentences. Think of them as details in your pictures of the facts. Each sentence expresses a thought, and thoughts, properly speaking, must obey the rules of logic (just as hands must conform to their skeletal structure). To draw a convincing human figure, you must be able to draw the head, the torso, the legs, the feet, the arms and hands. And to draw a hand, you must be able to draw fingers and thumb and palm and wrist. Likewise, your model of organizational culture may include artifacts, values, and assumptions. But can you write two sentences about each of these notions that distinguish them from the ordinary, commonsense meanings of the words? Do your sentences capture, not only the sense that Edgar Schein gave to them, but also their underlying interconnection, i.e., the way they “add up” to a culture? Can you put all this together in a single paragraph of seven or eight sentences whose key sentence is “Edgar Schein (2017) posits three levels of organizational culture”? Can you then isolate each sentence and make (at least some) sense of it?

Try it. And then try to describe an actual organization in those same terms. “The organizational culture of XYZ Corp. was disintegrating.” The absolute state of it! Write two sentences about the state of the artifacts, another two about the company’s values, an then a couple about its assumptions. Make them as clear as you can and as detailed as you need. Make sure that the paragraph supports your overarching claim of that the company’s culture is in trouble; but make sure, also, that each sentence alludes to the underlying structure that is coming apart, the logic of XYZ’s disintegration. Again, write seven or eight sentences. Try long ones and short ones and simple ones and complex ones. “Try them all,” as Senior says of his materials (pencil, charcoal, pens, brushes, and all kinds of paper). “Each one will be a means of revelation concerning your subject. And the only true comprehensive answer to as to ‘How to…’ is the simple instruction ‘Get on with it.'”