"The essential thing in a poet is that he build us his world."

(Ezra Pound)

"Discipline is implied."

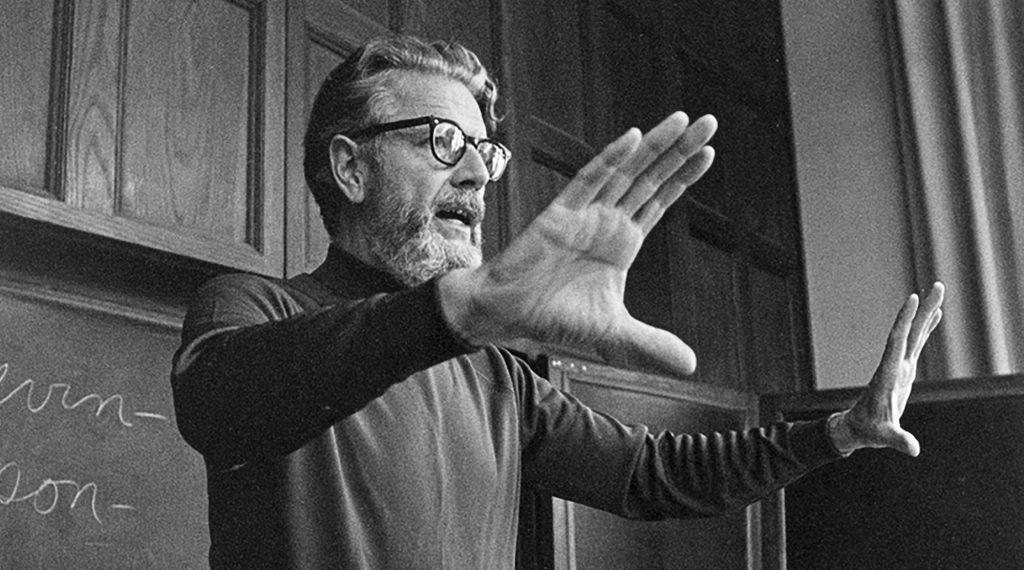

(William Carlos Williams)

Ludwig Wittgenstein famously begins his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus with a simple but sweeping proposition. “The world is everything that is the case,” he declares. The reader will later be told that this proposition is actually meaningless; it is not a statement “about” the world at all. It just shows us what the words mean. We might say it defines the word “world”, but surely it also defines “everything” and “being the case”. None of these words are especially technical — we all knew what they meant before we read the sentence — but he commits us to a certain relationship between them. They don’t represent a fact; they show us the logic of language. Interestingly, he will go on to claim (just as meaninglessly, he would argue) that the logic of language is the same thing as the logic of facts, the logic of the world.

His mentor, Bertrand Russell, has summarized this idea in a sentence that has never left me since I read it many years ago. “The essential business of language,” he said in his introduction to Wittgenstein’s treatise, “is to assert or deny facts.” On the face of it, this claim seems less certain than Wittgenstein’s opening statement, though he presents it with the same assured feeling of logical truth. We can push back against it a little by asking, What about the “business” of demanding and denouncing acts? I.e., surely the normative functions of language are as “essential” as its empirical functions? And Wittgenstein himself would indeed eventually abandon any reduction of language to any particular “essence”; language is used for so many different things that it seems odd to give statements of fact some sort of priority. What about asking questions, for example? What about expressing feelings?

In his notebooks, Wittgenstein once remarked that beginning the Tractuatus by invoking “the world” was a kind of conjuring act, a magic trick, an attempt to get us to imagine something that can’t actually (or in fact!) be imagined. He should perhaps have started, he went on, with “this tree” or “this table”, i.e., things that actually exist and can be seen and talked about meaningfully. “We make ourselves pictures of the facts,” Wittgenstein had said elsewhere in the Tractatus, and we can certainly imagine a tree, we can picture it, much more clearly than we can imagine “the world”. If we stuck to simple imagery — trees, rain, birds — perhaps philosophical problems would never arise? That is one way of putting Wittgenstein’s philosophy.

Will you allow a little poetry? Here’s a poem that Jonathan Mayhew recently drew to my attention.

The trees--being trees

thrash and scream

guffaw and curse--

wholly abandoned

damning the race of men--

Christ, the bastards

haven't even sense enough

to stay out in the rain--

That’s William Carlos Williams. He’s the one who also pointed out how “much depends upon” red wheelbarrows glazed with rainwater. His friend, Ezra Pound, believed that “the arts provide data for ethics,” the materials out of which to construct a worldview, a moral universe. Can they also provide data for epistemology? Can they help us to understand the logic of representation, the rules by which we make pictures of the facts? Can they help to imagine the structure of the world? These days, after all, we poor bastards hardly even go outside, let alone to stand in the rain. I’m going to devote a few posts to this subject, if you’ll bear with me.