I’m back from my leave and looking forward to talking to scholars and students about their writing again. As always, I will be pursuing it as a “craft” that can be developed through practice. I’ve been putting the final touches on my main activities for this semester and I thought I’d share them today for those who are interested. You will notice that registration is open only to CBS students and staff, but if you would like to participate in something and are not part of the CBS community feel free to contact me to see if that might be possible. Some of these activities have an online option, and that will usually be a quite open channel. You can get an overview here.

As a new thing this year, I’ve decided to address some ordinary “pedagogical” issues. What can we do to improve ourselves as students, as learners? There’s a definite art to this, which is situated in some rather familiar conventional contexts, aptly captured in the title of Norm Friesen’s The Textbook and the Lecture, or what I sometimes simply call “the academic situation”. This situation provides a number of reliable resources for learning, and, of course, a number of dependable challenges to overcome. For example, it provides us with an orderly framework within which to think, which risks becoming a set of constraints on our creativity. We are encouraged to be precise, but there’s a risk that we’ll be bored. That tension is virtually constitutive of academia.

The “Art of Learning” series in the fall is intended as a kind of loose warmup to the more goal-oriented “Craft of Research” series in the spring. In the fall, we’ll talk about the various competences that together define what it means to be a “knowledgeable” person, what it means to have “learned” something. In the spring, we’ll bring these skills together in the work of researching and writing a year-end project or thesis. If a research paper is written “one paragraph at a time” an education proceeds through azure moments, “rooted in watching with affection the way people grow”. The talks will give me an opportunity to explain what I mean by this, not least to myself.

I don’t intend to make too much out of the distinction between “art” and “craft”, except that, to me, craftsmanship is more about the work that is produced and artistry is more about the experience that it produces. Somewhat clumsily, we might say that craft is more objective and art is more subjective. Craft is about whether the thing works, while art is about what it does to us. The reason they’re hard to keep apart, of course, is that a “work of art” works precisely when it moves us. And sometimes an encounter with plain old good craftsmanship is a transformative experience in itself. It’s a good thing I’ve a got a few weeks before I start, and many more to work though these issues one at a time!

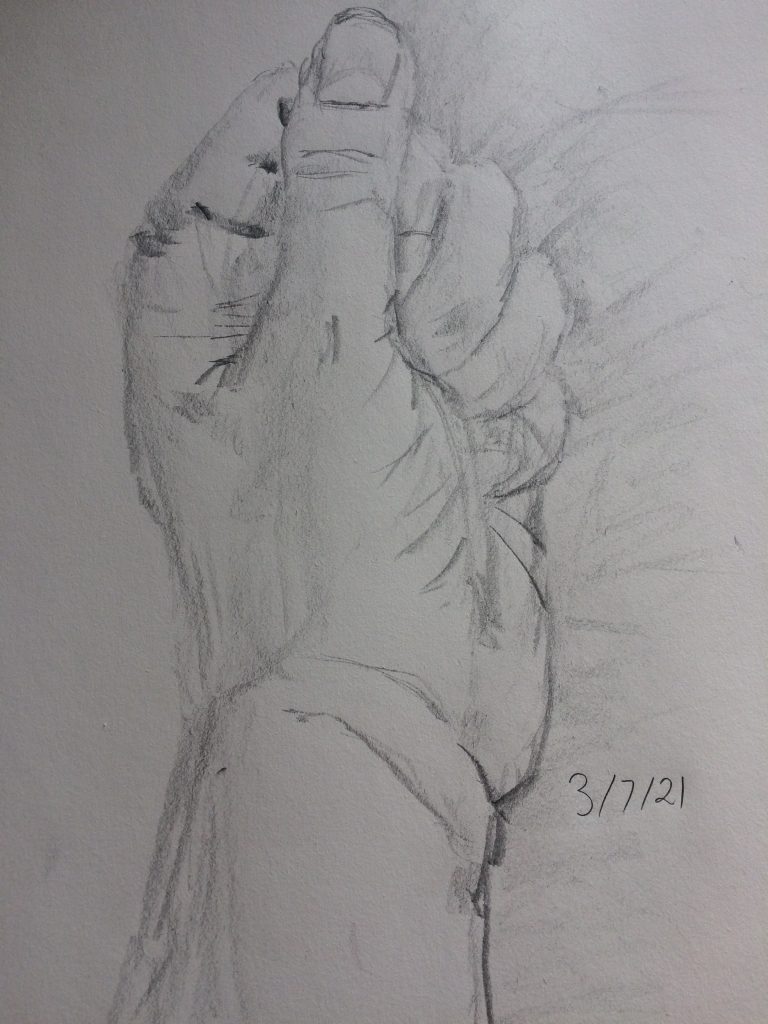

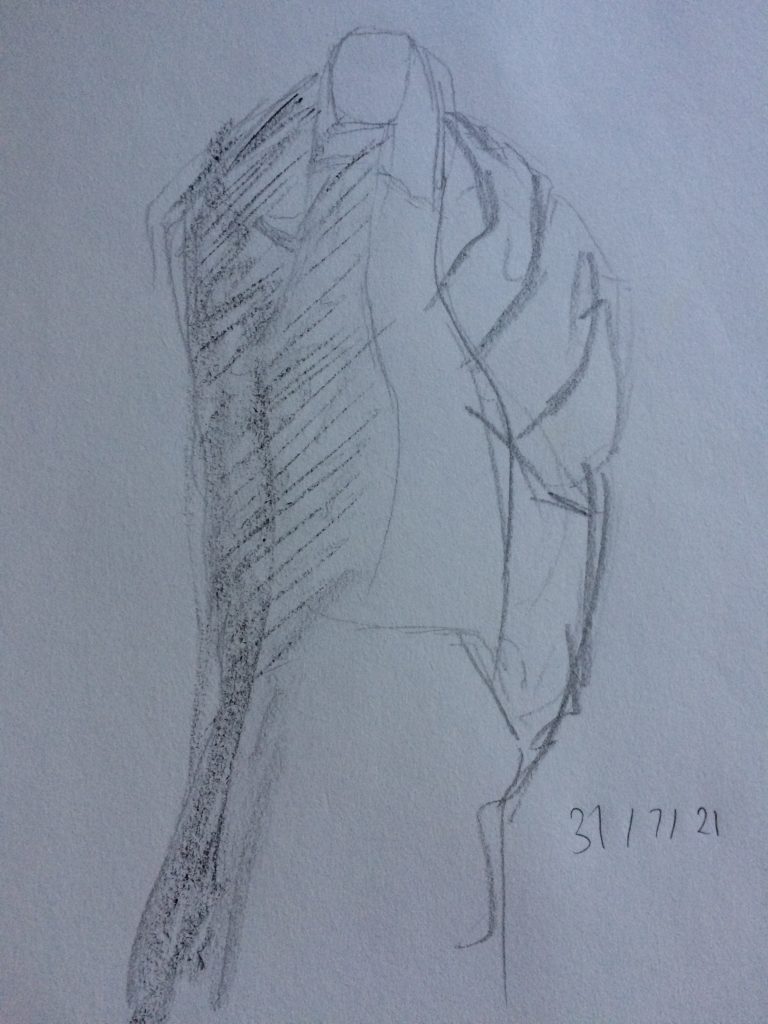

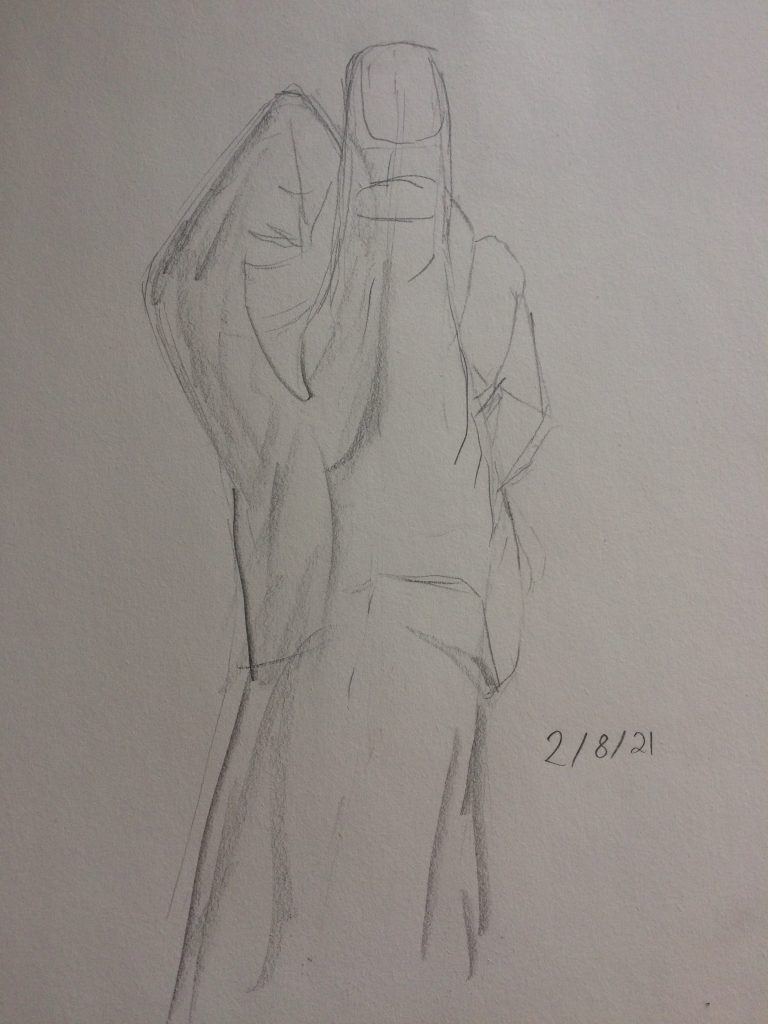

While I was on leave, I drew a lot of hands. My artist friend helpfully reminded me to draw, not what I know, but what I see. Even more specifically, she told me to begin with the shadows, not the lines. “The lines aren’t really there,” she said; “they’re just edges, where things end.” I have tried and tried but I’m still blinded by my knowledge from seeing my hand clearly. On some days I am proud of what I have accomplished, on others I am frustrated beyond consolation. On some days, I feel both emotions about the same drawing. I am far from mastering the craft of drawing anything, let alone the complex machinery of the hand. But I am learning.

“We suffer and we learn,” said Aeschylus. For many students, that’s all there is to it. You tough it out, you suffer through it, and you move on with your life. But what I want to suggest is that this suffering isn’t just what Oscar Wilde (writing from jail) called “one very long moment”. It is a series of discrete moments during each of which we find a specific kind of composure. We learn how to read and how to write, how to listen and how to talk, how to think and how, finally, to enjoy the whole business of knowing things, one experience at a time. We have to give ourselves the time to do this. We have to find a moment, and then another, and undertake to learn something from it. Under these conditions, guided by this discipline, I would argue that Whitman’s words hold true: “Whatever satisfies the soul is truth.”