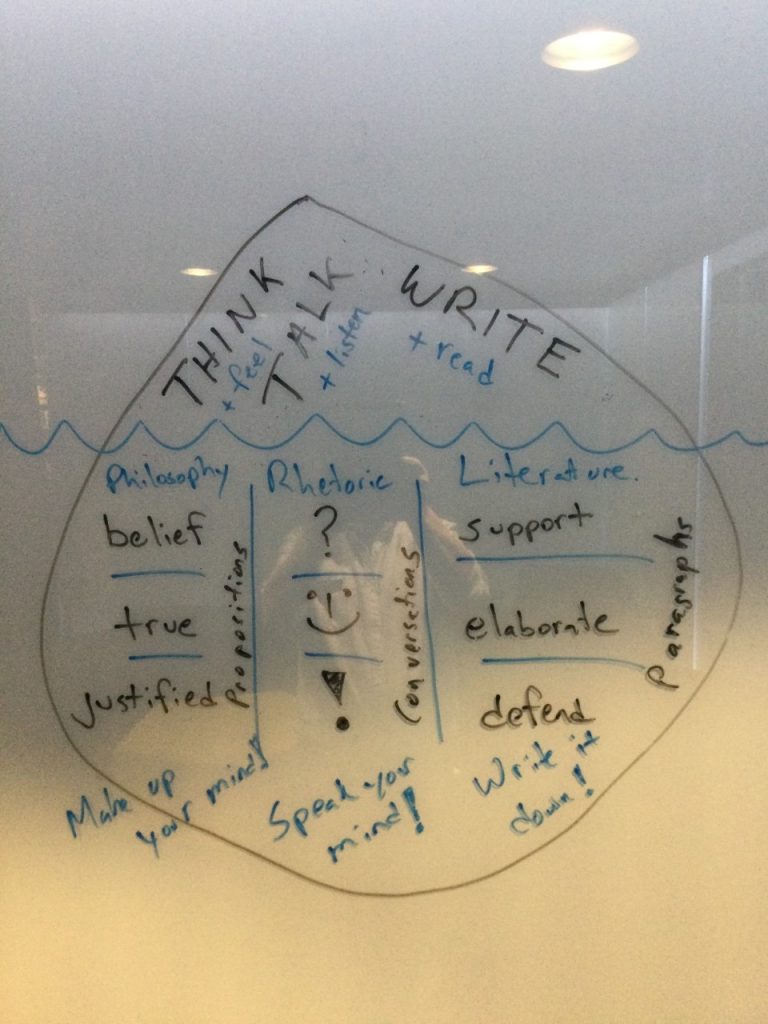

The Art of Learning series is off to a good start. My first talk, “How to Know Things,” went well, but looking at the notes from last year, I realized that I had forgotten to emphasize an elegant conceptual triad, or rhetorical triptych, so I thought I’d make up for it by writing a blogpost. The overarching message of the talk is that knowledge is a competence that supports a performance. Being knowledgeable (“for academic purposes”) about something means being able to think, talk, and write about it more effectively than someone who is not. Under the surface of these performances is a deep foundation of philosophical, rhetorical, and literary skills that allow us to make up our minds, speak them, and write them down. “The dignity of the movement of an iceberg,” Hemingway reminds us, “lies in only one eighth of it being above water.” In an academic setting, it is our knowledge that gives dignity to our propositions, our conversations, and our paragraphs, which deploy but never completely exhaust our cognitive resources.

When we make up our minds we form beliefs. Philosophers describe beliefs as “propositional attitudes”, which, like hopes, fears, and desires have “propositional content”. We believe that something is the case, just as we might fear, hope, or wish that it is the case. The content of our belief is what we think is true and we call this what a “proposition”. The essential thing about a proposition, however, is not that it actually is true (if it’s something we fear then we hope it isn’t!) but that it could be true or false. Unlike individual words, as well as questions and commands, propositions have a “truth value”. They’re either true or false. In academic settings, we want much of our writing to express propositions because they’re the content of our knowledge, they capture what we know, one truth at a time. If you’ll permit a pun, academics must have a propositional attitude, they must comport themselves towards the world as something that can be articulated in propositions. They must see the world largely as a collection of facts that make propositions true or false.

These propositions then come up in conversation. To be knowledgeable in an academic setting is to be able to hold your own in a conversation with other knowledgeable people. You have to understand their questions, get their jokes, and respect their boundaries. You have to say what you think in such a way that others can and will keep talking to you about it. You have to understand how to contribute to their thinking, and how to let them contribute to yours. Kleist talked about “the gradual formation of thought while speaking,” and although it has been argued that he was perhaps not being wholly serious (more on that some other time), there is no question that scholars and students can only claim to know things if they are willing to discuss them. Scholars are expected to present their work at “colloquia”, i.e., meetings where they “speak together”. Students are sometimes required to take oral exams. A knowledgeable person should be able to demonstrate that they are “conversant” in their subject matter.

Academics, after all, do not deal in isolated propositions that are simply true or false. They hold their beliefs in “webs” that sustain them holistically. We can believe any one thing only because we believe many other things; and if we change our mind about some things we usually have to change our minds about others. That’s why scholars and students should be able to compose themselves in paragraphs such that some propositions support, elaborate, or defend other propositions. That’s one way we can make the relations between our beliefs perspicuous and help to keep track of the consequences we would face if we turned out to wrong. We recognize that some propositions are more difficult than others and our paragraphs are composed to use some propositions to make other proprositions easier to believe, understand, and agree with. (Belief is not the only thing that is hard about a proposition.) Composing paragraphs and putting them together in essays and papers, is the characteristic way that scholars commit their thoughts to a logical structure. They literally put their thinking in writing.

Think, talk, write! Make up your mind, speak your mind, write it down! Propositions, conversations, and compositions. Propose, converse, compose! Some people think rhetorical triptyches like this are trite and easy.* But they can serve as both heuristics and mnemonics for university students (and faculty!) who are trying to learn difficult material in a way that they’ll retain long after they finish their studies, long after they’ve gradually perfected their thoughts and graduated (do you see what I did there?). And if you want to sketch the outlines of an 8000-word paper in, say, under 1000 words, why not write five paragraphs that “conceptualize, analyze, and discuss” your object … one, two, three. Remember that Plato’s Academy was a garden. It’s easier to imagine in panels.

(Source: Wikipedia)

_____

*You may have noticed that this really a nested 3 x 3 triptych. Propositions are (1) justified, (2) true (3) beliefs; conversations require (1) questions, (2) humor, and (3) boundaries; paragraphs (1) support, (2) elaborate, or (3) defend a knowledge claim. It’s all very neat and tidy.